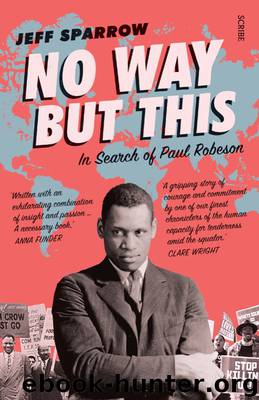

No Way But This by Jeff Sparrow

Author:Jeff Sparrow

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: BIO002000, POL004000, HIS037070, POL042000, BIO032000, BIO005000, HIS056000, SOC054000, HIS045000, HIS032000

Publisher: Scribe Publications

Published: 2017-02-20T05:00:00+00:00

A few days before I left Wales, I caught a lift with Beverley’s friend Patrick Jones, from Pontypridd to Mountain Ash. He was a poet, and Beverley had asked him to run workshops in the local schools, helping the kids compose their own responses to the Robeson exhibition.

It was about fifteen minutes’ drive between the two villages, and along the way we talked about the Welsh attitude to the mining past. I mentioned how Harry Ernest had been shaking his head about the state of choral music. Harry was a great aficionado of Welsh choirs, he’d explained. But the music came, of course, from the mines and the chapels. And now the mines were gone and the chapels were in steep decline, with many of the local churches struggling to keep their doors open. It was hard, I said, to avoid a sense of loss.

‘Oh, there’s definitely a lot of nostalgia,’ Patrick said. ‘I guess the harsh conditions forged a spirit of solidarity, of looking after each other. And people remember that.’

I could see why they would. What were the lines from the poet W.H. Davies? ‘Such sorrow in the valley has,’ he wrote in ‘The Collier’s Wife’, ‘made kindness grow like grass.’

The Pontypridd History Society maintained a little museum, a small collection of curiosities and artefacts pinned on walls and beneath the glass of dusty cabinets. There was an oil painting of a pigeon named Springfield Boy, annotated with his victories from 1932 (the bird had come second in Shrewsbury; third in Chester; second in Lancaster; and so on). There were portraits of eisteddfod winners: men with serious faces and generous moustaches, posed like victorious football teams. There was an array of miners’ lamps, displaying an almost Darwinian evolution of the technology from candles to electric bulbs. There was a scale model of a colliery; there was a banner from the National Union of Mineworkers Cwm Llantwit Lodge.

A whole way of life had depended on coal. A whole way of life had been uprooted when the mines closed.

Patrick laughed. ‘What they forget, though, is that things weren’t actually so great.’

Outside the car, the hills passing by were iron red when the light hit them, and the green of the trees changed from chartreuse to viridian. But, of course, that was because the slag heaps had gone and the shafts had been filled in and the harsh scars gouged by the collieries rendered almost invisible.

Patrick dropped me off in the centre of Mountain Ash, near where a sign advertised the Mountain Ash Workman’s Club and Institute. I stopped for a while at a statue honouring the legendary eighteenth-century runner Guto Nyth Brân, who’d been captured in bronze outpacing a weary hound. The streets in Mountain Ash were very similar to those in Pontypridd, lined with rows of little cottages, all adjacent to one another in long terraces. There was something comforting in their solidity: they were small, but they felt permanent and substantial, in a way that modern dwellings wouldn’t, with each house embedded in the stone and in the community.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37491)

Still Foolin’ ’Em by Billy Crystal(36046)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32064)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31459)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31409)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26244)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22769)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18636)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18329)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17113)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16695)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(14763)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(14749)

Molly's Game by Molly Bloom(13888)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13781)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13689)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(12807)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11794)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(11624)