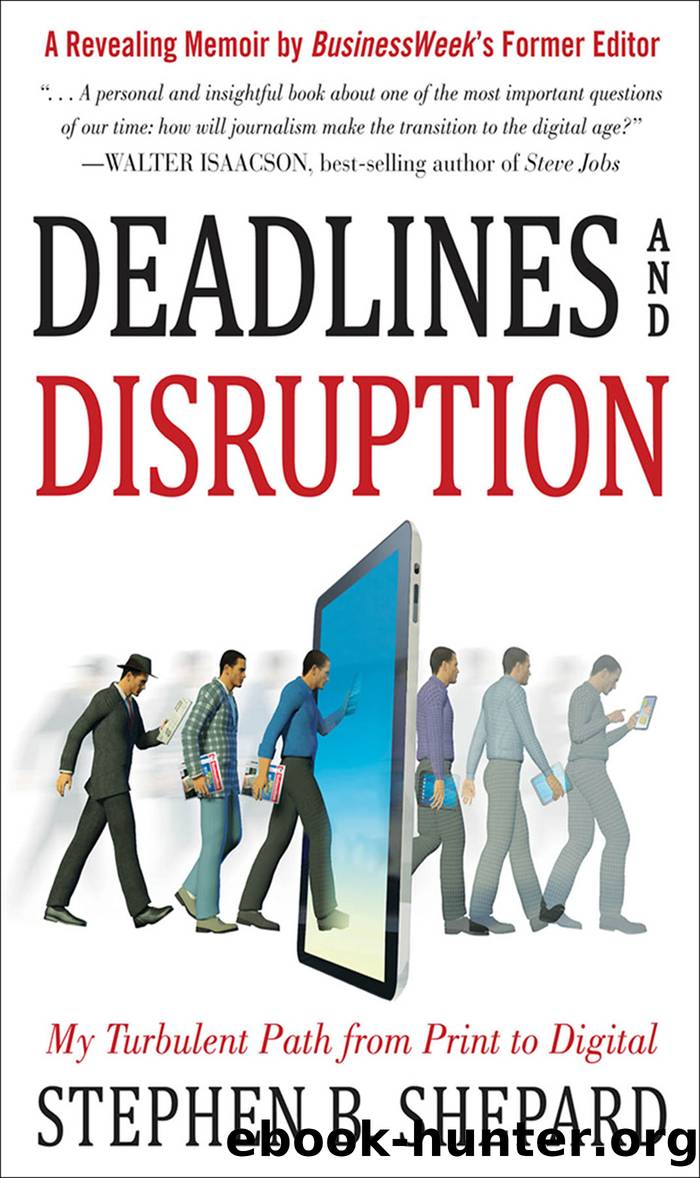

Deadlines and Disruption by Stephen B. Shepard

Author:Stephen B. Shepard

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: McGraw Hill LLC

Published: 2013-10-15T00:00:00+00:00

18

The Internet Boom and the New Economy

As the Internet boom turned tidal in the late 1990s, the notion of a New Economy took hold, and BusinessWeek was smack in the middle of it. The phrase meant different things to different people, but in our view, the concept centered on a higher level of efficiency, or productivity, enabled by the new digital technologies. The Internet made communications easier and cheaper, creating a truly global village in which people around the world were only a click away. It converted information into digital bits, instantly transporting nearly all intellectual property, from books to music, to users everywhere. It connected buyers and sellers at lower cost in ways never before possible. It enabled established companies to flatten their management hierarchies, while permitting start-ups to flourish by lowering their barriers to entry to a marketplace. In short, while disruptive to some, as new inventions always are, the Internet tended to make business more productiveâto lower costs, to reach more customers in more places, to get more output for less input of capital or labor.

To economists, this sort of productivity gain has always been the holy grailâthe best way to raise a nationâs standard of living without triggering inflation. In postwar America, roughly during the 1950s and 1960s, the economy was remarkably efficient, churning out productivity gains of about 2 to 3 percent a year. Though the United States encountered the usual cyclical ups and downs, wages grew nicely, jobs were ample, and inflation was modest. Suddenly, in the 1970s and 1980s, productivity growth stalledâdown to about 1 percent a year. Economists debated the reasonsâfrom the Vietnam War to higher oil pricesâbut everyone agreed that low productivity growth was a bad thing.

The Internet promised to reverse the decline, and intuitively it made sense. But the productivity numbers remained discouragingly low well into the late 1990sârecalling the famous quip by MIT economist Robert Solow, a Nobel Laureate: âYou can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.â1 At BusinessWeek, our economics editor, Mike Mandel, who held a PhD in economics from Harvard, began writing a series of articles about a ânew economy,â in which growth was driven by technological change. In effect, he wrote, the business cycle was no longer dominated by such traditional industries as automobiles, housing, steel, and chemicals but rather by digital technologies. And since these new technologies increased efficiency, Mike argued that the productivity gains were real. Why was this so important? Because higher productivity gains would allow the economy to grow much faster without triggering increased inflation. And faster economic growth meant more jobs, increased wages, and higher corporate profits. He spelled all this out in one of his early cover stories, âThe New Business Cycle,â published in the issue dated March 31, 1997.

If I had any doubts, they were soon erased by the persuasive arguments of Fed Chair Alan Greenspan. Based on his own analysis of the data and conversations with business executives from many different industries, he came

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37751)

Still Foolin’ ’Em by Billy Crystal(36319)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32514)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31920)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31905)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26574)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23046)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19010)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18546)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17379)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16825)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15831)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15278)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14451)

Molly's Game by Molly Bloom(14116)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14027)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13706)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13262)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12344)