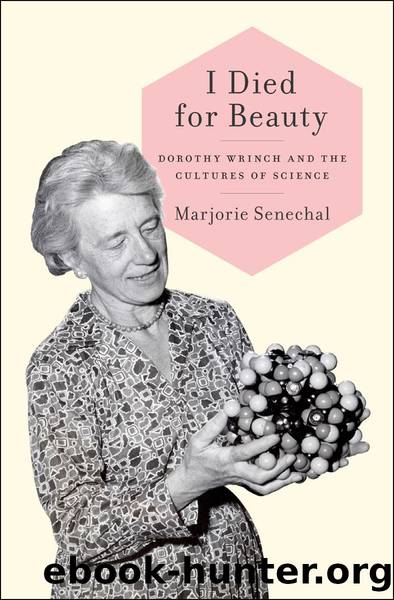

I Died for Beauty by Senechal Marjorie;

Author:Senechal, Marjorie;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press, Incorporated

Published: 2012-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

The cyclol hypothesis introduced the simple assumption that the residues function as four-armed units, and its development during the last few years has shown that this single postulate leads by straight mathematical deductions to the idea of a characteristic protein fabric.⦠These cage molecules explain in one simple scheme the existence of megamolecules of definite molecular weights, of highly specific reactions, of crystallizing, and of forming monolayers of very great insolubility.18

True, he said this to an audience of physicists, but it wasnât just physics-speak: he nominated Delta for a Nobel Prize in Chemistry that year (no, she didnât get it).19

Harold Urey studied in Copenhagen after receiving his Ph.D. The busy Bohr assumed he was a physicist and Urey never set him straight. When he wrote to his thesis director, G. N. Lewis in Berkeley, for help in finding a job, Lewis tried to park him in a physics department. âLewis likely saw Urey as too mathematically oriented for his liking as a chemist,â says Patrick Coffey in Cathedrals of Science.20

Ross Harrison argued that âsuccessful explanation in embryology had to be measured by âsimplicity, precision, and completeness of our descriptions rather than by a specious facility in ascribing causes to particular events.ââ21

Niels Bohr felt it as he spun uncertainty into gold. In Einsteinâs words, âThat this insecure and contradictory foundation was sufficient to enable a man of Bohrâs unique instinct and tact to discover the major laws of the spectral lines and of the electron shells of the atoms together with their significance for chemistry appeared to me like a miracle ⦠This is the highest form of musicality in the sphere of thought.â22 Bohr agonized over the dark heart of physics. We were âreminded time and again by Bohr himself what the real problem is with which he struggles,â his friend Paul Ehrenfest wrote in 1923, âthe unveiling of the principles of the theory which one day will take the place of the classical theory.â23

But for Linus Pauling, mathematics was a tool and nothing more. âMathematics was fine as a tool,â says Thomas Hager in Force of Nature.24 He quotes Pauling, âI could never get very interested in it. Mathematicians try to develop completely logical arguments, formulating a few postulates and then deriving the whole of mathematics from these postulates. Mathematicians try to prove something rigorously. And I have never been very interested in rigor.â

Young Dorothy Crowfoot, quaking with trepidation at the prospect of graduate study in x-ray crystallography, wrote to her parents, âIt is one thing to appreciate the structures that other people have worked out for crystalsâand quite another to be able to work them out yourself. The first requires the same faculties I apply to mosaicsâthe second requires pure mathematics. It is quite dreadful to think about it.â âDespite the good progress she was making,â Georgina Ferry says in Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life, âDorothy became downhearted by the end of the first term, convinced that her old bugbear, mathematics, was letting her down.â25 She stayed the course, pursued protein structure for 30 years, and won a Nobel Prize in 1964.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37509)

Still Foolin’ ’Em by Billy Crystal(36082)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32098)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31495)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31440)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26280)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22786)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18668)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18345)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17128)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16700)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(14901)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(14813)

Molly's Game by Molly Bloom(13903)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13832)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13723)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(12842)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11851)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(11790)