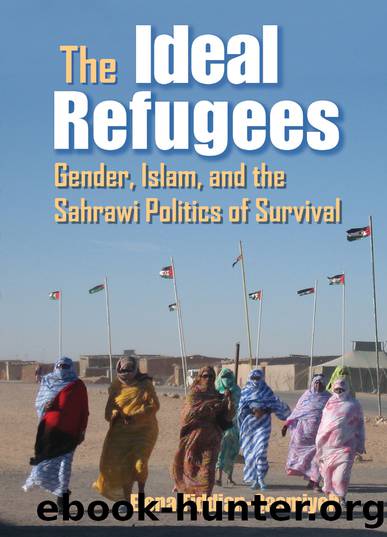

The Ideal Refugees by Fiddian-Qasmiyeh Elena;

Author:Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Syracuse University Press

Published: 2018-08-09T00:00:00+00:00

1. All translations from Spanish and French are my own, unless noted otherwise.

2. Blank 1999; Abu-Rabia 2006; Hamdan 2007; Scott 2007.

3. EFE 2007; Vargas-Llosa 2007.

4. Sturcke 2006; Tempest 2006.

5. On âsavingâ Afghan women from the burqa, see Abu-Lughod 2002; Hirschkind and Mahmood 2002; Rutter 2004; Stabile and Kumar 2005, 766ff; Kandiyoti 2007b.

6. It appears probable that Khira Mohamed does not personally consider the milḥafa to be a religious item, since, while she may wear âtraditionalâ clothes in the refugee camps, she does not wear the milḥafa while in Spain, nor (given the journalistâs question) does she wear the hijab. Veiling has been common among Christian, Jewish, and Muslim women in the Arab world (El-Guindi 2003, 595) and elsewhere (Küng 2007, 620â621), thereby highlighting the cultural and religious significance of the veil beyond Islam.

7. Both before and after donning the milḥafa I discussed different forms of veiling practices and interpretations of the Qurâan with the women and girls who were determined that I should veil. Referring to my experiences of working in Egypt and Syria, I indicated that some Muslim women and men in the Middle East and Europe believe that, while Muslim women should dress modestly, they were under no obligation to wear the veil. The response to my proposal was categorical: I was told that all Muslim women are obliged to veil, and that it is haram not to do so.

8. Lindisfarne-Tapper and Ingham provide a detailed examination of the diversity of clothing and veiling in the Middle East (1997).

9. In the Spanish context, the term âveloâ is commonly used to refer to both âthe veilâ in abstract, and the hijab qua veil more specifically. Hence, Vargas-Llosa directly equates the hijab with what he refers to as the âIslamic veilâ (2007).

10. Any recognition of (for instance) Tunisian laws passed since 1981 against Muslim women wearing the veil in public institutions (including universities) is absent from the official discourse.

11. On Sahrawi girlsâ participation in the transnational educational network, see Fiddian-Qasmiyeh 2009.

12. According to the NUSWâs meeting with Spanish delegates, ten women were elected to represent each dÄâira (district), resulting in eighty to ninety women representing each wilÄya (camp) at the National Congress. They had previously discussed the issues debated in the National Congress on both neighborhood and camp levels.

13. Since the late 1970s, Sahrawi girls have studied in Algeria, Cuba, Libya, Spain, and the former USSR. They have not, however, participated in the Syrian educational program, which is solely for young men attending university, nor, to the best of my knowledge, in the more recently established Qatari program.

14. The predominance of older women in social and political activities outside of the khayma is common in Bedouin groups. It is also in line with the above-mentioned tendency to allow for less-strict veiling of menopausal or postmenopausal women.

15. Verbatim proceedings, NUSW meeting with Spanish delegates, 27 February Camp (April 2007).

16. I would argue that older women often have a greater level of security than younger women, allowing them to be vocal or

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spell It Out by David Crystal(36109)

Life for Me Ain't Been No Crystal Stair by Susan Sheehan(35800)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32543)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31939)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31928)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31915)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29648)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19037)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

Twilight of the Idols With the Antichrist and Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche(18618)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15936)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15328)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14481)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13885)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13344)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13343)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13230)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12183)