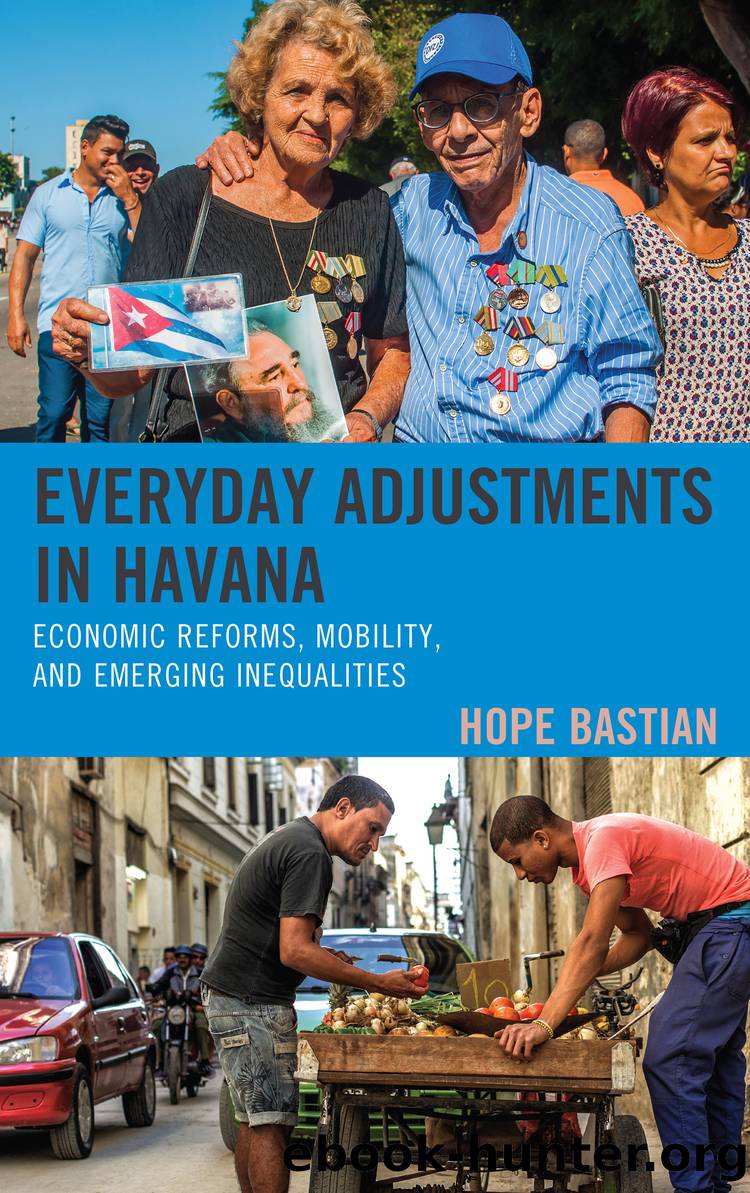

Everyday Adjustments in Havana by Bastian Hope;

Author:Bastian, Hope; [Bastian, Hope]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lexington Books/Fortress Academic

Published: 2018-05-24T00:00:00+00:00

Consumption in Cuba

Given the methodological complexity, Cuban social scientists on the island frequently approach the issue of economic inequalities by studying differences in levels of consumption and consumption practices. In Cuba today, where the largest sources of income in most households come from non-salary sources (of varying shades of legality) it is difficult to approach the study of inequalities by tracking income. There is a refrain in Cuba that explains that âThe streetsmart lives off the dummy/honest man, and the dummy/honest man lives from his workâ [El vivo vive del bobo y el bobo de su trabajo]. When you ask people in Havana how much they earn in salary at their state sector jobs they are very willing to share what they earn, both in informal social conversations and formal research interviews. Sharing of how ridiculously low their salaries are seems to produce a cathartic effect. Talking about low salaries is like talking about the weather, itâs something that is experienced by everyone. However, when I attempt to follow up by asking about non-salary benefits, or what the búsqueda is, the questions go unanswered, unless there is a high level of rapport.

Very few studies have been successful in quantifying the scale of income inequalities in Cuban society today. CIPS researchers provide a survey of research on economic inequalities and the different scales used to compare income groups in Cuba, and point out the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies (Espina Prieto et al. 2003). Katrin Hansing and Manuel Orozcoâs 2012â2013 survey of 300 remittance recipients with small businesses includes a table with information on their reported monthly income from sales (Hansing 2014).

Cuban-American economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago published estimates of monthly incomes in several occupations in 1995 and again in 2002 (Mesa Lago 2002, 7). Mesa-Lagoâs data includes tables with estimated monthly incomes in several occupations in the state and private sectors, based on a dozen interviews with recent Cuban visitors and immigrants in Madrid and Miami in the spring of 2002. When comparing these numbers, he claims that there is a significant expansion in income inequality; however, he does not explain the units that he is comparing, making the data difficult to scrutinize (Mesa Lago 2002, 7). In a 2015 issue of Temas, Cubaâs premier social sciences journal, actually not released until May 2017, Mesa-Lago attempts to establish a comparison between average wages and pensions in the state sector and what he claims are conservative estimates of income from remittances and private sector activities. According to his data, the yearly income of the average remittance recipient ($411 CUC) is 6.1 times more than the average pensioner ($67 CUC).

He claims that the yearly income of a person who rents a home to tourists ($77,500 CUC) is 1,156 times more than the average pensioner. In his calculations of the annual income of a person renting to tourists, he takes the example of a person renting a seven bedroom, seven bath mansion with a pool which he says goes for $5,000 CUC per week. This example is far from typical.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spell It Out by David Crystal(36108)

Life for Me Ain't Been No Crystal Stair by Susan Sheehan(35798)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32538)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31936)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31912)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29647)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19032)

Twilight of the Idols With the Antichrist and Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche(18618)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15927)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15326)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14477)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13875)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13342)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13333)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13229)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12183)