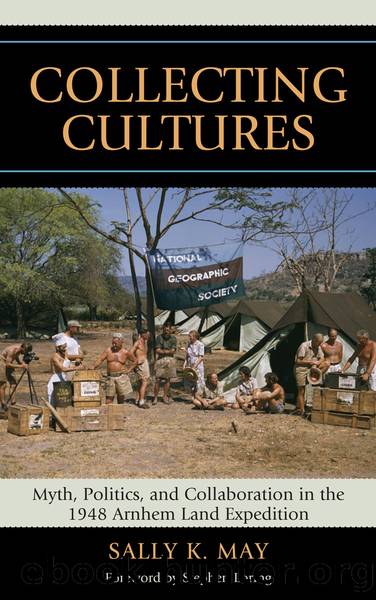

Collecting Cultures by May Sally K.;

Author:May, Sally K.;

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 467169

Publisher: AltaMira Press

NOTE

1. The Berndts first visited Oenpelli in 1947 but their longest period of fieldwork took place from December 1949 to May 1950 (see Berndt and Berndt 1970).

7

Collecting Arnhem Land

Tom Griffiths (1996: 25) has argued that collections suppress their own historical, economic, and political processes of production. This is true of the Arnhem Land Expedition ethnographic collection, and it is one of the underlying aims of this book to address this issue. This chapter, therefore, reviews the processes involved in the shaping of the collection and the contemporary social attitudes that contributed to collection strategies. In other words, this is an exploration of mid-twentieth-century influences on the expeditionsâ field collecting. While it could be argued that individual collector preferences were the key factor in the types of objects collected, the influence of society and culture on the views of the collectors cannot be ignored. As stated previously, individual researchers were carrying mandates from their government and their cultural institutions and were, in essence, collecting for humanity.

In Australia, early researchers often collected ethnographic material culture from Aboriginal communities with what could be referred to as a Social Darwinian view. Many believed these Aboriginal cultures (or culture, as they believed at the time) represented an earlier form of Western culture. With a few notable exceptions, until the 1950s, researchers of Australian Aboriginal culture generally collected with the underlying assumption that their study group was an unchanging people with unchanging material culture (Trigger 1989: 141). As Murdoch stated in 1917, âThe dark-skinned wandering tribes⦠have nothing that can be called a history⦠change and progress are the stuff of which history is made: these blacks knew no change and made no progress, as far as we can tellâ (Attwood and Arnold 1992: x).

The result of this belief was that ethnographic collections were formed and used for studying what were assumed to be static, prehistoric cultures. Researchers saw this ethnographic material as providing them with the absent data in the archaeological record. It was believed that the gap resulting from perishable material not surviving in the archaeological record could be filled with modern ethnographic material (McBryde 1978). Though the question of Australiaâs static culture prior to European colonization was called into question by researchers such as Norman Tindale in southern Australia, interest in cultural change and regional variation did not mark Australian archaeology until the 1950s, particularly following the advent of radiocarbon dating (Trigger 1989: 143).

With colonization and the significant impact that this had upon Aboriginal cultures worldwide, people began to see Charles Darwinâs predictions of Aboriginal cultures becoming extinct as becoming fact (Darwin 1871: 521). Though at first the devastation of other cultures was accepted as progress, eventually fear of losing something irreplaceable began to enter the minds of the colonizers.

Simpson described the âAustralian Aboriginalâ as âa patient who years ago was marked down as âdyingâ and whose treatment since has consisted mainly of pillow-smoothing and doses of pityâ (1951: 186). This fear led to urgency in recording and preserving and was the overwhelming

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spell It Out by David Crystal(36105)

Life for Me Ain't Been No Crystal Stair by Susan Sheehan(35792)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32533)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31931)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31922)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31907)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29644)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19027)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19010)

Twilight of the Idols With the Antichrist and Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche(18611)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15906)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15316)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14472)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14042)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13837)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13338)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13325)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13224)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12179)