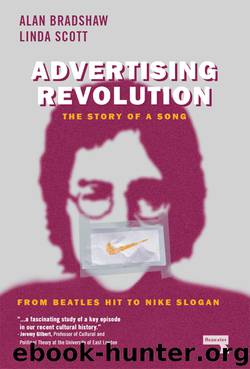

Advertising Revolution by Alan Bradshaw

Author:Alan Bradshaw

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Watkins Media

Conclusion

Both the “Revolution” songs and the “Revolution” ads emerged from an abrupt shift in the troc for their particular genre – music on the one hand, and advertising on the other – a move from blatant commercialism toward art. Both times, the genre was becoming eclectic, ironic, parodic, and highly allusory, but also political. Both the ads and the songs were produced by a collaboration of commercial authors – and before it was over, both the Beatles and Nike could “sell anything with their name on it”. Both were criticised for the high prices of their products. Yet both groups saw themselves as rebels or artists, and neither identified with business suits. In both cases, the texts were moving in the direction of the troc, even to the edge of the horizon of expectations, and thus predictably provoked ridicule, offense, and confusion in some quarters, as well as applause in others. In both cases, however, the offense was related more to a breach of the normal boundaries of commerce than to the constraints of form. In 1968, pop largely remained apolitical, and where it was taken seriously as political discourse, namely in the underground media, it was only permitted to be such if the message was sufficiently radical. By 1987, many felt that the Beatles’ music, a hyper-commercial form in its time, had become sacred; so the Nike commercial produced a similar schism, between those who still saw the Beatles as a commercial band and enjoyed having their influence celebrated and those who were strongly invested in the post-Beatles Lennon myth and felt the commercial defiled his memory. Thus, each text produced broadly bimodal responses that could be explained by the perceived authorial intentionality of John Lennon toward both politics and commerce.

This analysis raises questions about the role of memory, attitude, and involvement in the response to an advertisement. The memory that determined the response was not productrelated; it was tied to deep-rooted historical, political, cultural, and musical memories. These memories were indeed highly emotionally charged, but some people’s memories were the polar opposites of others – and in many cases, memories had substantially changed over time. Therefore, we could not assume that a well-loved song would automatically transfer to a positive attitude, as reported, for instance, for The Big Chill. Furthermore, these complex, contentious memories were the result of focused, repeated listening and interpretation at the first moment of the release of the “Revolution” songs. So, the question of involvement was not a matter of manipulating the present audience setting, but of an intense past experience. The heavy intertextuality and crossover of references – to other Beatles’ songs, but also to music videos, fashion, films, and the like – undermines any notion that the main cognitive action is manifest in the hard form of the text. This would be true even for children, since the video referred to a contemporary set of MTV signs, while the sound was clearly seen, even by a twelve-year-old, to refer to the songs of a previous generation.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Aircraft Design of WWII: A Sketchbook by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation(32192)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31251)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20351)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18813)

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18504)

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17637)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17314)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16933)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16882)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16601)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14497)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14325)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13953)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13479)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(12954)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11709)

The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon(8863)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8791)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8769)