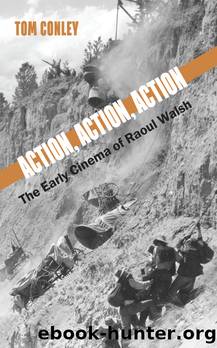

Action, Action, Action by Tom Conley

Author:Tom Conley

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: State University of New York Press

Published: 2022-06-15T00:00:00+00:00

6

Me, My Gal, My Brother

Me and My Gal

So you waited until they locked my brother up, and then you ran out on him, eh?

âBaby Face Castenega (Noel Madison)

Oh, Whatâs this? A brother act or somethinâ?

ââPopâ Riley (J. Farrell McDonald)

What about my brother?

âDuke Castenega (George Walsh)

ALTHOUGH SMALL WHEN SEEN next to The Big Trail, without a doubt Me and My Gal (1932) stands high and strong among the features Walsh directed at Fox Studios in the early 1930s. A pre-code film, a far cry from the epics and the war trilogy Walsh had directed at the cusp of the silent and sound eras, it emerges from a group of remarkable features, now in near oblivion, historians and cinephiles may be most likely to appreciate. Titles include The Man Who Came Back (1931), The Yellow Ticket (1931), and Wild Girl (1932). Wild Girl begins in the shadows of the sequoias where The Big Trail ends. Me and My Gal can be said to begin where Wild Girl leaves off and to end where The Bowery (1933) begins. Wild Girl features a racy Joan Bennett, the not-so-bashful blonde of âSalomyâs Janeâs Kiss,â the driving character in a memorable short story by Brett Harte (1836â1902). A stunning ingénue endowed with a shapely frame (displayed in a daring sequence of skinny dipping) and caustic wit, Salomy never minces words with her suitors. When she finally wins Billy (Charles Farrell), the lover of her choice, whom she saves from being unjustly hanged, her dreams come true.

Shot immediately afterward, Me and My Gal pairs an urban wild girl who makes good, another blonde Bennett, with a young Spencer Tracy, who meet in a diner (where else in the Depression?), perhaps around Fulton Street (or where young Owen Kildare had been an ice crusher in Regeneration), in Lower Manhattan. Where Wild Girl casts its players in the shadows and clefts of redwoods, Me and My Gal places its dramatis personae in confined or contained spaces: the edge of a pier, at the tables and counter of a crowded chowder house, near the doorway to a police precinct, at the entry and counter of a haberdashery, in a modestly furnished apartment, or in a crammed loft. Like Wild Girl and other titles of this moment in Walshâs career, Me and My Gal takes inspiration from the novelty of sound along with the visual style and manner of silent cinema. In this feature, at once immediately and accessibly (and very soon after in The Bowery), signature effects emerge from what the director does in mixing the two modes and their technologies.1

In âThe Evolution of Film Language,â a canonical essay of the postwar era that considers epochal transformationsâthe rift, reversal, and revolutionâthe seventh art is said to have undergone in the shift from silent to sound, André Bazin (1999, 63â80) contends that great directors, the real auteurs are (or now were) those who adapt silent composition to sound film. For Bazin, trained in land science and geography, the long take and deep focus define the spatial and temporal virtues of the seventh art.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Still Foolin’ ’Em by Billy Crystal(36329)

Spell It Out by David Crystal(36098)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31898)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29641)

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh(21607)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20465)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19020)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18996)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15295)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14615)

Molly's Game by Molly Bloom(14119)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14037)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13640)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13287)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12354)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12176)

The Break by Marian Keyes(9346)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9261)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8944)