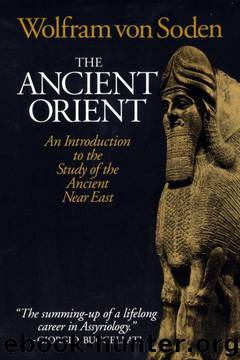

The Ancient Orient: An Introduction to the Study of the Ancient Near East by Wolfram Von Soden

Author:Wolfram Von Soden

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2010-12-07T17:02:00+00:00

i. The Sumerian Science of Lists as a Science of Order

oon after the invention of their writing system (see above, IV.i), the 'Sumerians began to compile smaller lists of cuneiform signs. With a system of word signs, sign lists are simultaneously word lists, having even a certain somewhat topical material arrangement. With the gradual transition to cuneiform, the signs, which were increasingly employed as syllabic signs, were becoming less pictorial. Thus, lists arranged according to the signs could remain simultaneously word lists with a topical arrangement of the signs only in the case of a minority of signs. For this reason, distinct lists of objects were created as early as the third millennium. These contained primarily compound words: in addition to objects designated by determinatives (see above, IV.i), including those objects made from wood, reed, leather, metals, stone, wool, and so forth, the lists enumerated plants with particular subgroups, such as trees and grains, as well as domesticated and wild animals, and certain classifications of people with designations for body parts, geographic names, stars, and divine names. The tendency toward a firmly established sequence within the individual groups, however, had still not been fully realized by the Old Babylonian period. Among the local scholastic traditions, which from the beginning had diverged widely from one another, that of Nippur came increasingly to prevail after the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur.' The word lists migrated to some extent with the writing system to both Elam and Syria, where independent native traditions developed, as the archives of Ebla (about 2400) impressively show, though they preserve the adopted lists in a form which has undergone manifold changes.

When such lists were first compiled, practical criteria may have stood in the foreground, and these always retained a great significance for the scribal schools. At the same time, however, these considerations were increasingly surpassed by goals of a more theoretical sort. The Sumerians believed in a means of ordering the world which brought with it confirmation of the working of the gods (see below, XII.2). The lists had the task of making this order manifest in connection with the main groups of objects and living creatures, including the gods. This could be accomplished, however, only by people who knew how to handle the lists. The Sumerians were unable to present their ideas in a connected fashion, either in the realms of nature, abstract matters, and theology, or in those of mathematics (see below, XI.9) or jurisprudence. Thus, Sumerian science lacked the conceptual framework of formulated principles (what in the West has been called "natural laws"), and simply ordered nominal expressions one after the other in a one-dimensional fashion, without any kind of elucidation. Verbs in finite form and abstract terms are found only in those sign lists which are not topically ordered, but not in the lists which have been ordered according to systematic criteria. Mythic literature served to illustrate the conception of order (see below, XIII.3). During the Neo-Sumerian period, the compilers and tradents

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3306)

The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (The Princeton History of the Ancient World) by Kyle Harper(3062)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2734)

Ancient Worlds by Michael Scott(2682)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2674)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2573)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2463)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(2451)

MOSES THE EGYPTIAN by Jan Assmann(2412)

The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (7th Edition) (Penguin Classics) by Geza Vermes(2277)

The Earth Chronicles Handbook by Zecharia Sitchin(2227)

Lost Technologies of Ancient Egypt by Christopher Dunn(2224)

24 Hours in Ancient Rome by Philip Matyszak(2079)

Alexander the Great by Philip Freeman(2065)

Aztec by Gary Jennings(2023)

The Nine Waves of Creation by Carl Johan Calleman(1916)

Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World by Gager John G.;(1860)

Before Atlantis by Frank Joseph(1849)

Earthmare: The Lost Book of Wars by Cergat(1825)