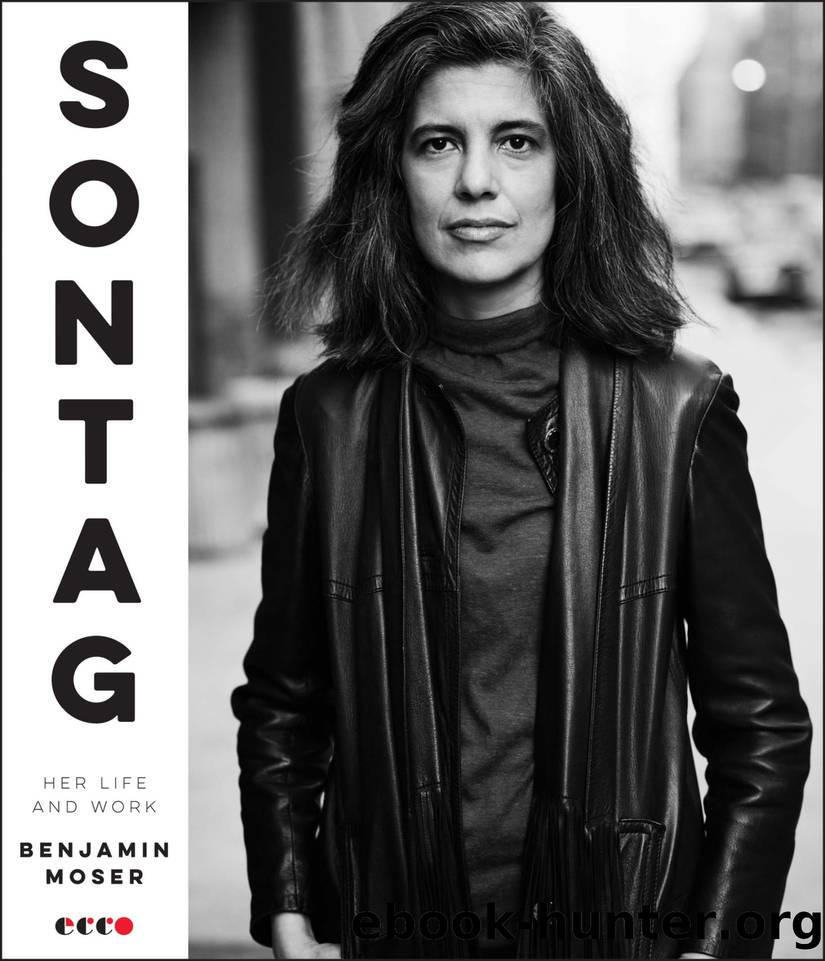

Sontag: Her Life and Work by Benjamin Moser

Author:Benjamin Moser

Language: eng

Format: mobi

ISBN: 9780062896391

Publisher: Ecco

Published: 2019-09-17T07:00:00+00:00

Chapter 26

The Slave of Seriousness

In public, the postcancer Sontag was invulnerable. From the end of the 1970s, she held court alongside other grandees (Brodsky, Derek Walcott, Donald Barthelme) at the New York Institute for the Humanities, whose members gathered to hear visiting speakers and discuss their own work. Sontag, with the white streak in her hair, was one of the Institute eminences, and visitors often marveled at the combative wit and intelligence on display. “At one point Susan took great offense at something I had said and turned on me in full force,” said the Australian writer Dennis Altman, “a majestic if rather terrifying experience.”1 This was the Sontag, majestic and terrifying, whose raised eyebrow made and broke careers, who penned essays like “Fascinating Fascism,” who knew everyone and everything.

But another Sontag was writing fiction whose main principle might be called narrative uncertainty. The uncertainty she introduced into her early novels and films was befuddling. Her insistence that nothing could be known—of her characters, of the events that befell them—made those works impossible to engage emotionally. The reader resented being thwarted by theoretical gimmickry, and only the devout, one suspects, read or watched to the end.

Uncertainty was a frustrating principle around which to organize a story. But when shifted from the narrative to the narrator, it approached truth by the same means previously used to mask it. The actual woman behind the increasingly formidable Sontag persona was profoundly uncertain. When this Sontag—not the one who fell back on rude assertion or artsy “Marienbad” theorizing—allowed uncertainty to seep into her writings, those writings invariably gained in resonance and authority. The results resembled the lists that litter her journals, or the collages of the surrealists, or the boxes of Joseph Cornell: fragments, in their shattered—which is to say their authentic—form. Life is lived in a cloud of unknowing; experience, memory, and dreams are never more than shards.

The book she published in 1978, I, etcetera, collected eight such stories, all of which had been written before her illness: from a time when she could still allow herself uncertainty. Dedicated to her mother, to whom she remained intermittently close, it opened, quite literally, with Sue. Written when she thought she was not going to China, “Project for a Trip to China” gathered what she knew of her father: snippets of memories, clumps of sentences, ample blank space. This kaleidoscopic approach, facts and aphorisms heaped up without attempting to force them to any totalizing revelation, was a feature of her best essays. These did not attempt, as in the Riefenstahl essay, to assert or to damn. Instead, they expressed a desire to revive the dead (her father); to “think about the unthinkable” (Artaud); to define the indefinable (camp). These writings do not shut off discussion. They leave it open, stimulate it; and stimulating discussion is the function—the achievement—of the great critic.

* * *

I, etcetera is a story collection, but it is not really a collection of fictions, as the word is often understood: “Project for a Trip to China,” for example, might be described as a poetic memoir.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Crime & Criminals | LGBT |

| Special Needs | Women |

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18100)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13132)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12965)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10938)

Becoming by Michelle Obama(9309)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7284)

Educated by Tara Westover(7093)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(4624)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4437)

Hitman by Howie Carr(4392)

On the Front Line with the Women Who Fight Back by Stacey Dooley(4320)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4244)

Year of Yes by Shonda Rhimes(4131)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3927)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(3601)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(3291)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3280)

Patti Smith by Just Kids(3244)

How to be Champion: My Autobiography by Sarah Millican(3202)