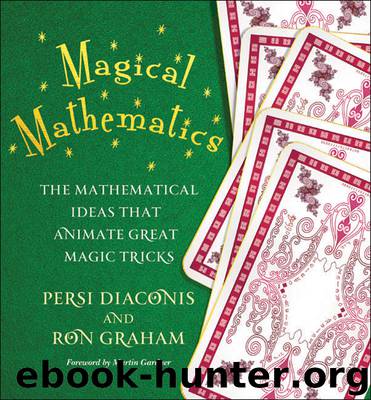

Magical Mathematics by Diaconis Persi Graham Ron & Ron Graham

Author:Diaconis, Persi, Graham, Ron & Ron Graham

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2012-03-14T16:00:00+00:00

PROBABILITY AND THE BOOK OF CHANGES

One of the mysteries in our lives is why the study of probability began so late in history. The earliest known systematic probability calculations appear around 1650 in the work of Pascal and Fermat. However, people have gambled in all sorts of ways for thousands of years. There were crooked dice and carefully made near-perfect dice. The ancients used strangely shaped dice made of sheeps’ knuckle bones. You would think somebody would have looked at these and said, “Maybe some sides come up more often than others.” We do find ample informal discussion of uncertainty as it appears in everyday life. In law, people had to combine evidence from uncertain sources and develop rough rules (for example, two witnesses were better than one, but not if the two were relatives). There were similar developments in medicine and religion. However, we have no record of people calculating odds or having a way to think about randomness other than “the machinations of the gods as seen by mere mortals.” James Franklin’s magnificent book, The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability before Pascal, is surely the best study of the prehistory of probability.3

The history of the study of probability in China is similar. In a careful historical study, Mark Elvin of the Australian National University documents the same issues.4 Gambling was prevalent, and there are comments about uncertainty in law, medicine, and commerce, but no calculations or theoretical framework for thinking about uncertainty.

The I Ching casts a new light on this mystery. The history of the I Ching is not without controversy. Knuth’s The Art of Computer Programming gives a mathematician’s history of the book.5 We believe the stick method of generating a random hexagram at least goes back to Confucius (551–497 BC). As described above, it uses a complex system of random divisions followed by a summation of “big/small” scores to wind up at a single straight or broken line. The probability calculations summarized in table 1 show that this procedure has been arranged so that the chance of a straight line is .

Similarly, the chance of a broken line is . The sophisticated procedure isn’t obviously symmetric. It takes some thinking for a modern reader to see the 50/50 chance. It took some sophistication to design it in the first place.

We explain where the numbers come from at the end of this chapter. One piece of the argument is worth mentioning now. To do any sort of probability calculations, some assumptions about what it means to “randomly divide a pile of sticks” is required. You can’t get probability out without putting probability in. Indeed, not everyone agrees that probability has anything to do with the I Ching. During a talk of ours on the I Ching at the New York Union Theological Seminary, one of the faculty members angrily protested our probability calculations: “What on earth does probability have to do with the I Ching? When I generate a random pattern to use the book by sticks or flipping coins, it is my hands that divide the pile or flip the sticks.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Dance | Individual Directors |

| Magic & Illusion | Reference |

| Theater |

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(18955)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(12831)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(6688)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(4583)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(4417)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4206)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4100)

Audition by Ryu Murakami(4093)

Call me by your name by Andre Aciman(4066)

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: The Journey by Harry Potter Theatrical Productions(3955)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(3913)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(3781)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(3578)

Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery by Eric Franklin(3483)

Apollo 8 by Jeffrey Kluger(3196)

How to be Champion: My Autobiography by Sarah Millican(3182)

Seriously... I'm Kidding by Ellen DeGeneres(3098)

Darker by E L James(3086)

History of Dance, 2E by Gayle Kassing(2997)