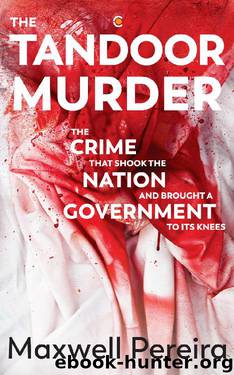

The Tandoor Murder by Maxwell Pereira

Author:Maxwell Pereira [Pereira, Maxwell]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Westland Publications Private Limited

Published: 2018-04-10T00:00:00+00:00

14

Corpus of Evidence

To almost any observer outside India, it might appear that the investigating team had all but completed its work at this point. We had the perpetrator in custody, we had a plethora of circumstantial evidence connecting him to the crime – and he had confessed to a number of senior police officers, even begging our forgiveness. To anyone not from the subcontinent, the successful prosecution of Sushil Sharma would have seemed a foregone conclusion.

Alas, that is not the order of things in the Indian judicial system. Aside from systemic challenges and the gamut of dirty tricks we could expect from Sushil, we would have to contend with a less-than-favourable provision of the Indian Evidence Act 1872.

The Act, which governs the admissibility of evidence in Indian courts of law, was originally passed by the Imperial Legislative Council during the British Raj. It has remained in force – substantially unchanged – since. A particular bugbear for the police is Section 25 of the Act which states, ‘No confession made to a police officer shall be proved as against a person accused of any offence.’

Essentially, this means an accused can confess to his heart’s desire in the police station – even before the commissioner of police – but this, in itself, cannot be presented as evidence of guilt before the court.

The intention of this provision was ostensibly to nullify the effect of police obtaining false confessions by coercion or third degree, or falsely claiming that they had received a confession from a suspect. How useful this provision is in restraining corrupt police personnel from incriminating innocent people is a moot point, though. A corrupt officer could just resort to other chicanery, such as doctoring evidence, to obtain a conviction.

For the honest, hardworking cop, Section 25 of the Indian Evidence Act 1872 is a handicap, especially when confronted with a cunning offender such as Sushil Sharma. To have a criminal freely confess to the police and then escape conviction may seem like a gross miscarriage of justice. But the investigating team knew this could very well happen with Sushil, despite his fulsome confessions to Niranjan, me, other interrogators, and even to Commissioner Nikhil Kumar.

This is not to say that we were legally hamstrung in our questioning of Sharma. Section 27 of the Act gives clear, if qualified, powers to the police to gather admissible evidence from a suspect. It states that ‘when any fact is deposed to as discovered in consequence of information received from a person accused of any offence, in the custody of a police officer . . . may be proved.’ If Sushil provided any information during questioning which led us to material facts or evidence, these and his information could be used to prove his guilt in court.

In short, we still had our work cut out for us. We would have to carefully prove our case with the evidence at hand. And we would have to persuade Sushil to tell us of, and lead us to, material evidence so that his statements would be admissible in court.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9313)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5766)

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5102)

Hitman by Howie Carr(5086)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4739)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4435)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4252)

Breaking Free by Rachel Jeffs(4214)

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann(4033)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3974)

American Kingpin by Nick Bilton(3872)

The Secret Barrister by The Secret Barrister(3690)

Molly's Game: From Hollywood's Elite to Wall Street's Billionaire Boys Club, My High-Stakes Adventure in the World of Underground Poker by Molly Bloom(3528)

Mysteries by Colin Wilson(3444)

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3374)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(3124)

I'll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara(3071)

Rogue Trader by Leeson Nick(3039)

Bunk by Kevin Young(2992)