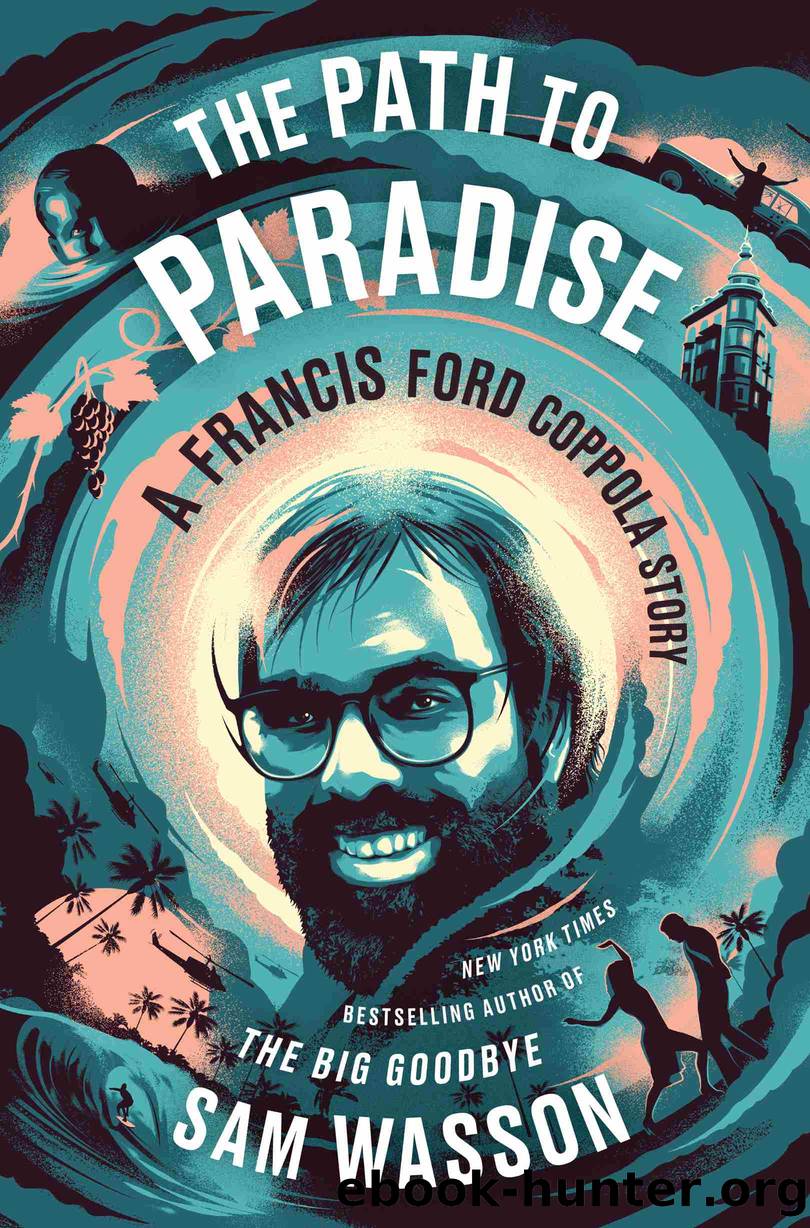

The Path to Paradise by Sam Wasson

Author:Sam Wasson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2023-10-13T00:00:00+00:00

II

THE APOCALYPSE

If a man could pass through Paradise in a dream, and have a flower presented to him as a pledge that his soul had really been there, and if he found that flower in his hand when he awokeâAy! And what then?

âSAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE, ANIMA POETAE

Apocalypse Now is not, as Coppola began it, a film about Vietnam. It isnât even about war. Nor did the philosophical play of good and evil Coppola had so arduously engaged survive his years-long reckoning with self and story. But where the film muddles, the psychic toll of Coppolaâs quandary is felt throughout. For all its spectacle, the venue of Apocalypse Now is interior. An impression of Coppolaâs private battle and Willardâs spiraling semiconsciousness, it is, at its best, a holy madness of sight and sound. Coppola never would find a worthy endingâindeed, there is no ending in the field of philosophical inquiry; at least, after thousands of years of searching, there hasnât been yetâbut the passions of the filmmaking ensemble, of Vittorio Storaro and Walter Murch, their pounding miasma of soaring color bombs and hypernatural audio environments, elevate the foundering Big Ideas of Apocalypse to what may even be a higher plane, rapture.

And so, for all the agony, the story of Apocalypse Now ends in ecstasy: Coppolaâs dream of Zoetrope really did come true, and on a scale only he could have imagined. More than just a production company, it proved to be a heightened awareness for all, a path to new frontiers of life and film.

For audiences, that is, Apocalypse Now is a film; for its filmmakers, a life. But for Francis Ford Coppola, it was a rite of passage. In his book From Ritual to Theatre, anthropologist Victor Turner locates the moment of ritual transformation in the juncture between chaos and order, what he calls âliminality,â the intermediary state of consciousness between oneâs old self and the new. The trancelike state of liminality can be literal or figurative, psychologically or socially evokedâas among the Ndembu of Zimbabwe, whose royalty are made to assume the role of commoner before they can assume the crown. But like any rite of passage, it is a grief, for it necessitates a killing of the old and dying self. In much of the psychological West, itâs called a nervous breakdown. Not everyone emerges intact, but those who do speak of being re-created. The same can be said for Coppolaâs creative process: literally, a process of self-creation. For only in losing himself in Apocalypse could Coppola beâand wasâreconstituted, found.

Looking back from the vantage of Apocalypse Now, it is evident that each of Coppolaâs personal works, his Zoetrope or Zoetrope-affiliated films, was likewise a rite of passage. Youâre a Big Boy Nowâits very title literalizing the first rite of passageâpreceded the first incarnation of Zoetrope, where Coppola was already beginning his processes of artistic and self-experimentation. In The Rain People, he retraced similar narrative territory, leaving home and family, this time with Natalie Ravenna, no longer a girl, married and with child: Youâre a Big Girl Now.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Actors & Entertainers | Artists, Architects & Photographers |

| Authors | Composers & Musicians |

| Dancers | Movie Directors |

| Television Performers | Theatre |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26591)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19030)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17398)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15921)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15324)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13850)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13303)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12362)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8965)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8908)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7663)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7544)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7315)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6194)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5407)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5367)