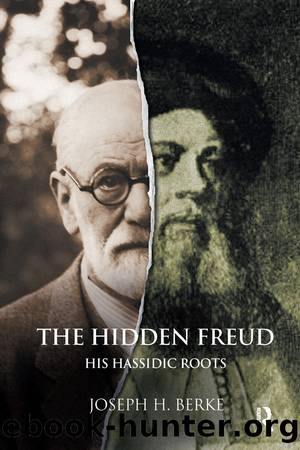

The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots by Joseph H. Berke

Author:Joseph H. Berke [Berke, Joseph H.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Psychology, General, mental health

ISBN: 9780429920998

Google: FBZWDwAAQBAJ

Publisher: Routledge

Published: 2018-04-17T20:46:21+00:00

And a second comment in the Zohar avows:

Come and see how intensely a person is attacked, from the day that the Blessed Holy One endows him with a soul to exist in this world! For as soon as a human being emerges into the atmosphere, the evil impulse lies ready to conspire with him_ âAt the opening [i.e., at birth] crouches sinâ (Genesis 4:7)âright then the evil impulse partners him ⦠because the evil impulse dwells within him, instantly luring him into evil ways. (ibid., Vol. 3, p. 85)

When does the yetzer ha-tov, the good inclination begin? The Zohar clearly establishes this at the age of thirteenâthe age of majority, at the time of a boyâs bar mitzvah. Yet, the great twelfth-century Jewish sage, Moses Maimonides (The Rambam) concluded that the good inclination/drive can be found only after the childâs intellect develops (2006, p. 324, fn. 45).

In contrast, the Aboth dâRabbi Nachman, an ethical treatise that is one of the fifteen minor tractates of the Talmud, insists: â⦠the evil inclination speaks, âSince I am doomed in the world to come, I will drag the entire body with me to destructionââ (chapter 16, p. 15a).

Given Freudâs extensive but disguised knowledge of Talmudic writings, one wonders whether he was aware of this passage and whether it could have been a prelude to Freudâs ruminations about the death instinct. It is striking that Freud had given a lecture to his Bânai Bârith lodge in 1915, entitled: âWe and Death.â He had initially thought of calling the talk, âWe Jews and Death,â in order to show the extent to which Jews are affected by destructive drives and fears about death. At that time Freud was addressing a specifically Jewish audience on aggressive instincts. In his earlier work (such as in Totem and Taboo (1912â13)) he had already begun to think about the connection between aggression and the death impulse. Obviously, Freudâs understanding of aggressive drives and death changed dramatically after the First World War.

The psychoanalyst Robert Hinshelwood elucidated the issue in his A Dictionary of Kleinian Thought: âHe [Freud] raised aggression to the same level of importance as the sexual drivesâin a strange way: by imputing to the human being an innate aggressive drive against his or her own existence, the death instinct.â (op. cit., pp. 327â328)

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9138)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(8447)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7889)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7848)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6941)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(5270)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4970)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4928)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(4784)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4743)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4589)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4479)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4357)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4323)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4208)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4137)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(4128)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3996)