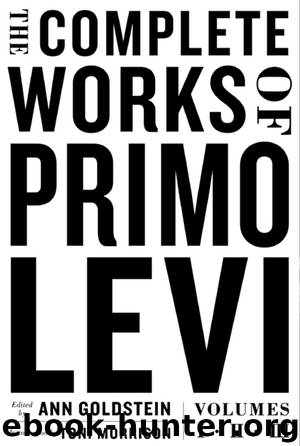

The Complete Works of Primo Levi by Primo Levi

Author:Primo Levi

Language: eng

Format: epub, azw3

Publisher: Liveright

The Gypsy

A notice was pasted to the door of the barrack, and everyone crowded around to read it; it was written in German and Polish, and a French prisoner, squeezed between the crowd and the wooden wall, struggled to translate it and comment on it. The notice said that, as an exception, all prisoners were permitted to write to their relatives, under conditions that were minutely specified, in the German manner. One could write only on forms that the head of each barrack would distribute, one for each prisoner. The only language permitted was German. The only addressees permitted were those who resided in Germany or in occupied lands or in allied countries like Italy. We were not permitted to ask for food packages but were permitted to give thanks for packages possibly received. At this point the Frenchman energetically exclaimed, “Les salauds, hein!” and broke off.

The uproar and the crowding increased, and there was a confused exchange of opinions in various languages. Who had ever officially received a package or even just a letter? And, besides, who knew our address, assuming that “KZ Auschwitz” was an address? And to whom could we write, given that all our relatives were prisoners in some camp, like us, or dead, or hidden throughout the four corners of Europe in fear of following our destiny? Clearly, it was a trick; the thank-you letters postmarked “Auschwitz” would be shown to a delegation from the Red Cross, or some other neutral authority, to prove that the Jews of Auschwitz were not treated so badly, given that they received packages from home. A filthy lie.

Three factions formed: not to write at all; to write without thanks; to write and thank. The partisans of the last argument (few, in truth) maintained that the business of the Red Cross was likely but not certain, and that a possibility existed, however slim, that the letters would arrive at their destination, and the thank-you would be interpreted as an invitation to send packages. I decided to write without thanks, addressing the letter to Christian friends who in some way would find my family. I borrowed a stub of a pencil, obtained the form, and prepared for the work. First I wrote a draft on a scrap of paper from a cement bag, the same I wore on my chest (illegally) to protect myself from the wind, then I began to rewrite the text on the form, but I felt uneasy. I felt, for the first time since my capture, in communication and in communion (even if only putative) with my family, and so I needed solitude; but solitude, in the camp, is rarer and more precious than bread.

I had the annoying impression that someone was watching me. I turned: it was my new bed companion. He was quietly watching me as I wrote, with the innocent but provocative gaze of a child, who doesn’t know the embarrassment of staring. He had arrived a few weeks earlier with a transport of

Download

The Complete Works of Primo Levi by Primo Levi.azw3

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Beautiful Disaster by McGuire Jamie(25018)

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh(21050)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(19934)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18225)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(14801)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(14784)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13806)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(12863)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12405)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11819)

Scorched Eggs by Childs Laura(11128)

The Break by Marian Keyes(9088)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8600)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8418)

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens(8341)

Never let me go by Kazuo Ishiguro(8338)

All the Light We Cannot See: A Novel by Anthony Doerr(8283)

A Man Called Ove: A Novel by Fredrik Backman(8201)

Circe by Madeline Miller(7822)