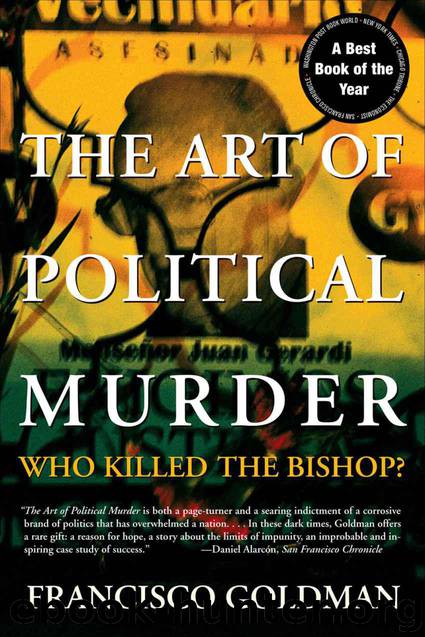

The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop? by Francisco Goldman

Author:Francisco Goldman

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Tags: Non-Fiction, Latin American History, True Crime, Guatemala, Politics, History

ISBN: 9780802118288

Publisher: Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Published: 2007-09-10T00:00:00+00:00

III

THE TRIAL

WITNESSES

I would have wished to live and die free, that is to say, subject to law in such a way that neither I nor anyone else could shake off the honorable yoke.

—Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “A Discourse on Inequality”

1

NO MILITARY OFFICER HAD ever been convicted of a human rights crime in Guatemala. Nor had any military man ever been charged with participating in a politically motivated crime of state such as extrajudicial execution, the crime for which the two Limas and Sergeant Major Villanueva were to be tried. Father Mario was accused of homicide and Margarita López of having withheld evidence. The trial, which was to be heard by a three-judge tribunal, was delayed for over a year while the defense filed various legal motions. It got under way in March 2001, and I went down to Guatemala a few weeks later.

Mynor Melgar was the lead lawyer representing ODHA, which, as co-plaintiff on behalf of the Church, was permitted to assist the special prosecutor in the case against the military men—although not in the cases against Father Mario or the parish-house cook. “So far, in the context of what you can hope to accomplish in a Guatemalan courtroom, I think we’re doing well,” Melgar said to me when I arrived. “The crime laboratories here don’t have many resources,” he explained, “and there’s little capacity for doing good forensics. Usually, the only real evidence you take to trial is the testimony of witnesses. And people can buy witnesses, intimidate them, they can kill them. That makes trying cases in Guatemala very complicated.” Most of the important witnesses in the Gerardi case had made written statements and then fled the country.

Mynor Melgar had left the country too, along with his wife and children. In 1999, he spent nine months in Berkelely, California, studying at the University of California’s Institute of Latin American Studies and giving volunteer legal advice to Guatemalan immigrants in the Bay Area. But Melgar, unlike most of the other exiles, had returned. “How nice that you’ve come back just to die,” an anonymous voice said in one of the first of many threatening telephone calls he received. A few months later, in December 2000, a man held a pistol to Melgar’s head while he knelt in the bathroom of his own home, in the presence of his wife and two uncomprehending little sons. The intruder said that he wasn’t going to pull the trigger. He had been told just to issue a warning.

Melgar’s soft-spoken, cheerfully bantering manner hid a basically reserved nature and a composed and incisive intelligence. When he was intensely engaged, his face settled into an expectant, slightly bemused expression and his eyes held an avid glow. Melgar grew up in El Gallito, Guatemala City’s most notorious barrio, where cocaine and crack are sold openly in the dirt streets and where chop shops for stolen cars are dug like caves into the walls of ravines, their entrances covered by day with tin sheeting and brush. In accordance with

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9324)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5770)

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5105)

Hitman by Howie Carr(5089)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4741)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4435)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4262)

Breaking Free by Rachel Jeffs(4216)

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann(4039)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3975)

American Kingpin by Nick Bilton(3875)

The Secret Barrister by The Secret Barrister(3696)

Molly's Game: From Hollywood's Elite to Wall Street's Billionaire Boys Club, My High-Stakes Adventure in the World of Underground Poker by Molly Bloom(3529)

Mysteries by Colin Wilson(3447)

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3375)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(3130)

I'll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara(3082)

Rogue Trader by Leeson Nick(3039)

Bunk by Kevin Young(2993)