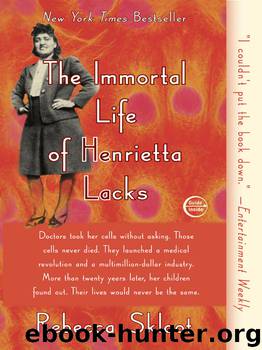

Rebecca Skloot by The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Author:The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks [Lacks, The Immortal Life of Henrietta]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

ISBN: 978-0-307-58938-5

Publisher: Crown Publishing Group

Published: 2011-03-08T06:00:00+00:00

With that paragraph, suddenly the Lacks brothers became very interested in the story of HeLa. They also became convinced that George Gey and Johns Hopkins had stolen their mother’s cells and made millions selling them.

But in fact, Gey’s history indicates that he wasn’t particularly interested in science for profit: in the early 1940s he’d turned down a request to create and run the first commercial cell-culture lab. Patenting cell lines is standard today, but it was unheard of in the fifties; regardless, it seems unlikely that Gey would have patented HeLa. He didn’t even patent the roller drum, which is still used today and could have made him a fortune.

In the end, Gey made a comfortable salary from Hopkins, but he wasn’t wealthy. He and Margaret lived in a modest home that he bought from a friend for a one-dollar down payment, then spent years fixing up and paying off. Margaret ran the Gey lab for more than a decade without pay. Sometimes she couldn’t make their house payments or buy groceries because George had drained their account yet again buying lab equipment they couldn’t afford. Eventually she made him open a separate checking account for the lab, and kept him away from their personal money as much as she could. On their thirtieth wedding anniversary, George gave Margaret a check for one hundred dollars, along with a note scribbled on the back of an aluminum oxide wrapper: “Next 30 years not as rough. Love, George.” Margaret never cashed the check, and things never got much better.

Various spokespeople for Johns Hopkins, including at least one past university president, have issued statements to me and other journalists over the years saying that Hopkins never made a cent off HeLa cells, that George Gey gave them all away for free.

There’s no record of Hopkins and Gey accepting money for HeLa cells, but many for-profit cell banks and biotech companies have. Microbiological Associates—which later became part of Invitrogen and BioWhittaker, two of the largest biotech companies in the world—got its start selling HeLa. Since Microbiological Associates was privately owned and sold many other biological products, there’s no way to know how much of its revenue came specifically from HeLa. The same is true for many other companies. What we do know is that today, Invitrogen sells HeLa products that cost anywhere from $100 to nearly $10,000 per vial. A search of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office database turns up more than seventeen thousand patents involving HeLa cells. And there’s no way to quantify the professional gain many scientists have achieved with the help of HeLa.

The American Type Culture Collection—a nonprofit whose funds go mainly toward maintaining and providing pure cultures for science—has been selling HeLa since the sixties. When this book went to press, their price per vial was $256. The ATCC won’t reveal how much money it brings in from HeLa sales each year, but since HeLa is one of the most popular cell lines in the world, that number is surely significant.

Download

Rebecca Skloot by The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(8328)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7259)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(7253)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6332)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(6055)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4208)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(4155)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4061)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4024)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3897)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(3827)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3819)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(3668)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3565)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3506)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(3447)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3433)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(3309)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(3276)