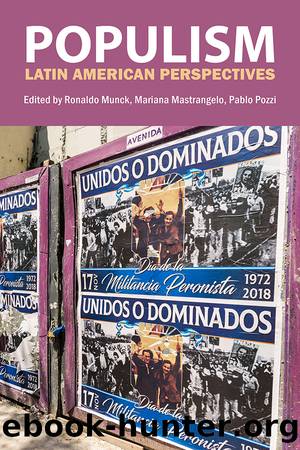

Populism by Ronaldo Munck;Mariana Mastrangelo;Pablo Pozzi; & Mariana Mastrángelo & Pablo Pozzi

Author:Ronaldo Munck;Mariana Mastrangelo;Pablo Pozzi; & Mariana Mastrángelo & Pablo Pozzi

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3)

Chávezâs programme of nationalization

A failed coup dâétat in April 2002 was closely followed by an employer-led general strike (known as the âoil strikeâ or âoil lockoutâ) in December 2002, carried out by the Puntofijista10 elites. The strike was a further failed attempt to overthrow the Chávez government, Resistance to that strike generated the rise of the workersâ struggle throughout the country. Its failure was taken as a victory by the sectors of Bolivarian workers who were beginning to organize independently, outside of the CTV (which was one of the organizers of the strike, together with Fedecámaras).

From 2003 onwards, Venezuelan workers took back companies that had been paralysed and demanded the nationalization/renationalization of industries in the hands of the national or foreign private sector. At the same time, the workersâ struggle began to try out novel forms of organizing productive activity through workersâ councils and workersâ control, proposals that found an echo in the Bolivarian government and ended up becoming state policies (López Sánchez 2017a: 34). Workersâ control, which emerged as a slogan for action during the 2002â03 strike, launched the slogans of âFactory stopped, factory occupiedâ and âWorkersâ control of productive activityâ, leading to the occupation by the workers of numerous companies that had ceased activity. This occurred in Venepal (Carabobo), Venezolana de Válvulas (Los Teques), Textiles Fénix (Guárico), Cristine-Carol Perfumes (Caracas), and others (López Sánchez & Hernández 2016: 184).

From 2004, when Chávez ordered the expropriation of Venepal, âWorkersâ Controlâ began to be considered a policy of the Venezuelan state, although it was only in 2009 that it was included as a government guideline, in what became known as the Guayana Socialist Plan (López Sánchez & Hernández 2016: 184). The aim of Workersâ Control as a policy was to achieve the full exercise of participatory and protagonist democracy by the workers, inside and outside the factory (Adarfio 2011: 43). It constituted an experiment in the workersâ battle to replace the bourgeois state with a new state of transition to socialism, and was designed not to repeat the fatal mistakes of the Soviet experience (Carcione 2010: 56).

Another aspect of workersâ organization was the Prevention Delegates and the Health and Safety at Work Committees (CSSL), whose promotion was in the hands of INPSASEL,11 an institute attached to the Ministry of Labour. These committees were set up throughout the country, in various companies, and in both public and private institutions, which made them an organizational tool almost as widespread as the trade unions themselves. Prevention delegates played a role as defenders of workersâ rights, especially in small companies, where there were no trade unions (López Sánchez 2017b: 201).

In May 2012, a new Labour Law (LOTTT)12 was passed, restoring the rights violated in the Caldera reform of 199713 and also incorporating a suite of new labour and political rights (López Sánchez 2017b: 234). The approval of the new LOTTT was seen as an outstanding legal contribution to the workersâ struggle against neoliberalism and against capitalist exploitation in general, according to the definition contained in

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Vikings: Conquering England, France, and Ireland by Wernick Robert(77321)

Ali Pasha, Lion of Ioannina by Eugenia Russell & Eugenia Russell(39320)

The Vikings: Discoverers of a New World by Wernick Robert(36484)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31339)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30936)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30892)

The Conquerors (The Winning of America Series Book 3) by Eckert Allan W(27808)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22174)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(16667)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16635)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(13873)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13061)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12936)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11907)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11889)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11886)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11261)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11053)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10910)