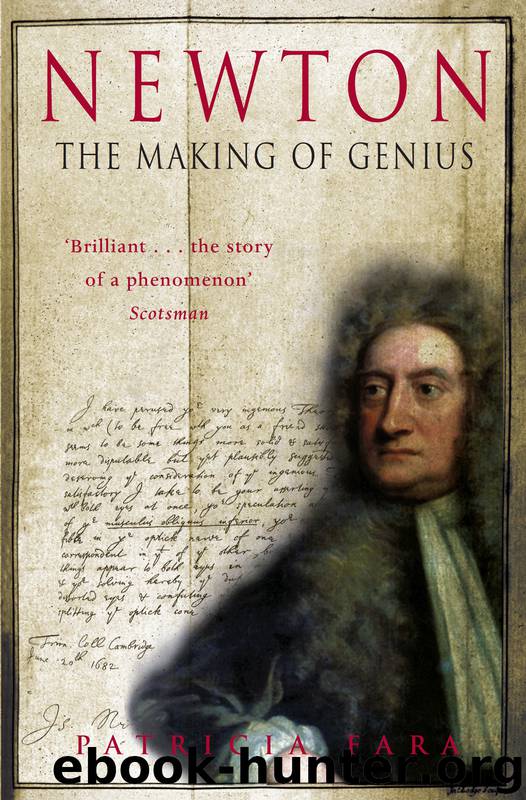

Newton by Patricia Fara

Author:Patricia Fara [Fara, Patricia]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781447204534

Publisher: Picador

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

Perhaps Hayley’s clumsy scansion in the last couplet indicates his emotional resistance to taking seriously her claims that she, too, could be a poetic genius.31

Invention and copyright

The London physician and author John Aikin marvelled at the mechanical geniuses he found working in the provinces. During his travels round Manchester, he derided James Brindley, the famous canal engineer, as an illiterate, ill-spoken peasant. He did, however, condone Brindley’s habit of retiring to bed for a couple of days when he had a particularly thorny problem to work out. ‘This is that true inspiration,’ wrote Aikin admiringly, ‘which poets have almost exclusively arrogated to themselves, but which men of original genius in every walk are actuated by, when from the operation of the mind acting upon itself, without the intrusion of foreign notions, they create and invent.’32

Aikin’s expression ‘original genius’ crops up in essay after essay. ‘The highest praise of genius is original invention,’ declared Samuel Johnson.33 At first glance, he seems to mean the same as Aikin, but Johnson’s celebrated quip comes from his Life of Milton. And that was the very nub of Aikin’s complaint – the accolade of original genius was reserved for Milton, Homer and Shakespeare. Aikin had been a prolific medical writer before he turned to more literary genres, which was perhaps why he took the unusual step of insisting that technological innovation paralleled artistic originality.

Many essayists on genius agreed with Young that ‘in all the arts, invention has always been regarded as the only criterion of Genius’.34 Confusingly, like ‘science’ and ‘genius’, the word ‘invention’ was also rapidly changing in the second half of the eighteenth century. For literary philosophers, invention was not about James Watt’s steam engines or Richard Arkwright’s spinning machines, but concerned plots, ideas and metaphors. Mechanical inventiveness had previously been rooted in its Latin meaning, ‘discovery’, so that inventors were regarded as finding and revealing God’s designs, rather than being praised for their own originality. Far from enjoying the high status they came to command during the Victorian era, innovative practical men were looked down on as mercenary craftsmen or opportunistic projectors. It was well into the nineteenth century before inventors and engineers started to gain some measure of security through the patent system. As late as 1834, Watt’s new monument in Westminster Abbey showed him in the traditional pose of a philosopher, seated and wearing academic robes. The inscription commemorated him not as a practical inventor, but as an eminent man of science who exercised his ‘original genius’ in ‘philosophic research’.35

In Newton’s lifetime, the ‘Man of Business’ had been distinguished from the ‘Man of Genius’ who ‘looks down with Contempt on the grovelling Creature whose Soul is confin’d to the same Circle with his Trade’.36 A hundred years later, the goals of wealth and truth were still divorced. Aspiring professional authors wanted to retain the distinctiveness of genius, since claiming originality bolstered their claims to ownership. Nevertheless, they were also wary of the taint associated with working for money rather than glory.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9115)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(8415)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7877)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7804)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6929)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(5252)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4946)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4942)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4919)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(4762)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4729)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4570)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4456)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4343)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4301)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4182)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4118)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(4115)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3973)