Indigenous London by Coll Thrush

Author:Coll Thrush

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2016-04-07T04:00:00+00:00

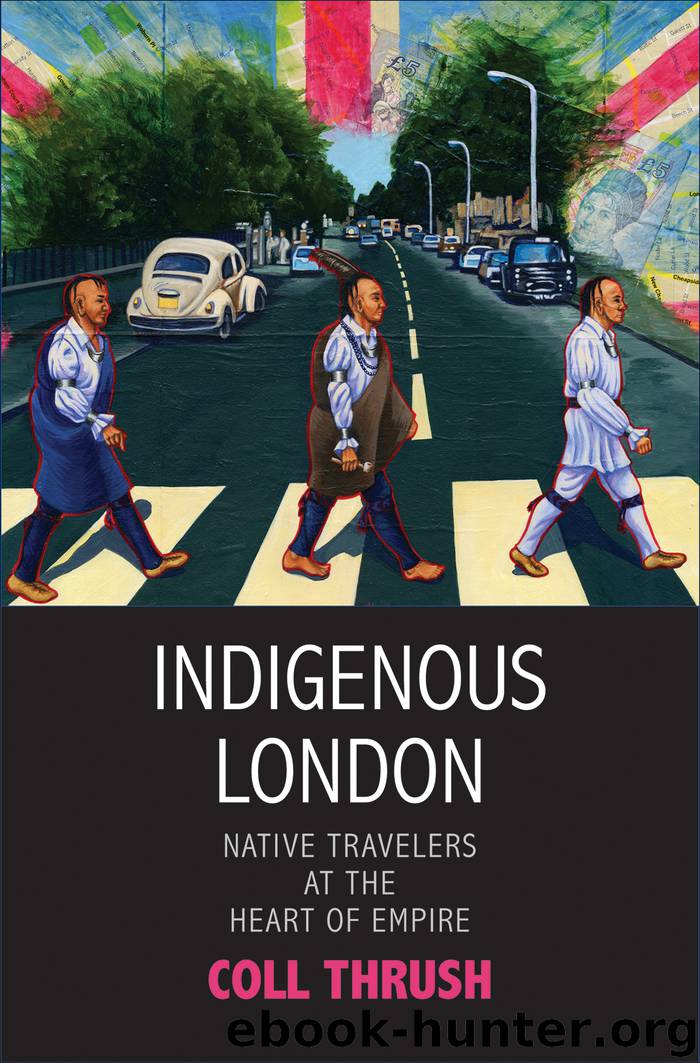

The Maori visitors of 1863 at the John Wesley House in City Road, in an oil painting by James Smetham. (Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection, no. NK138.ANL)

This string of travelers symbolizes not just a growing connection between Māori people and London, but also a deepening of colonization in their territories. The Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi), signed in 1840, dramatically transformed relations between Māori and Pākehā peoples, setting into motion confusions and conflicts over the treaty’s wording and meaning that continue to resonate today. One of the responses to the treaty and to accelerating alienation of Māori land was the Kīngitanga, or King Movement, in which some iwi sought to create a pan-Māori monarchy parallel to that of the British Crown, much to the consternation of Pākehā settlers and other Māori alike. Meanwhile, British settlement of the islands continued apace.54

This was the context for the Māori visit to London of 1863. The portrait of these people, made at the headquarters of the Wesleyan Missionary Society, was only one example of their high profile during their time in the city. Most of them were Christian converts, young people with names like Huria (Julia) and Horomana (Solomon).55 Two others were war leaders, and the elders among the group: Te Hautakiri Wharepapa and Reihana Te Taukawau. In all, there were six different iwi represented in the group, but such divisions would be downplayed during the journey. “We were told,” recalled one member of the group after their return home, “to put aside our quarrels, our bad words & all drinking & sin and live all together good & eat together & be together.”56 And in truth, there was likely a growing sense of togetherness at work here; although most if not all of the travelers had rejected the Kingi movement, which was uniting iwi across the North Island, they, like many other Māori people, were beginning to see the benefits of a pan-Māori movement in response to British presence. In their case, it meant a stated connection—even a kind of loyalty—to Wikitoria Te Kuini o Ingarani (Victoria, Queen of England). The man who chose them was an on-again-off-again missionary named William Jenkins (the Māori called him Toko Tikena, “Pole Jenkins,” because of his height). Horrified by the wars that had already rocked Aotearoa, Jenkins wanted to bring “respectable” Māori to Britain to further peaceful relations between the two peoples.57

Whatever their reasons for joining Jenkins’s venture, when the group arrived in London in the spring of 1863, Haromana, Wharepapa, and others were to have experiences while in the city that were like none they had ever had before. Upon their arrival, they were first housed at the Strangers’ Home in Limehouse, a modern facility established for non-European sailors and which the Māori called Te Whare Mangumangu (Negro House). Later, they would move to a house in Marylebone’s Weymouth Street, and finally to the decidedly more upscale Grosvenor Hotel in Belgravia. Throughout their time in the city they

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Vikings: Conquering England, France, and Ireland by Wernick Robert(79854)

Ali Pasha, Lion of Ioannina by Eugenia Russell & Eugenia Russell(40120)

The Conquerors (The Winning of America Series Book 3) by Eckert Allan W(37100)

The Vikings: Discoverers of a New World by Wernick Robert(36905)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32404)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31805)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31778)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22949)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18797)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18452)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15140)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14295)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14201)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13177)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13161)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13136)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12254)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11993)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(11895)