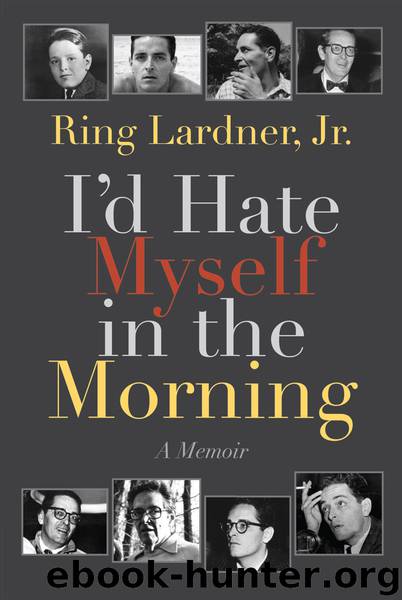

I'd Hate Myself in the Morning by Lardner Ring; Navasky Victor;

Author:Lardner, Ring; Navasky, Victor; [Lardner, Ring, Jr.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Easton Studio Press, LLC

Published: 2017-04-30T04:00:00+00:00

I had subscribed to and articulated all these positions; and my liberal friends had listened respectfully, as had I, to their counter-arguments. Now, however, the question was whether to support or oppose the war, and the debate was not so amicable. More people left the Party than joined it during these embattled years, yet the new recruits included my friend Dalton Trumbo, author of the stirring antiwar novel Johnny Got His Gun. Trumbo had resisted my previous recruitment efforts because of his strong pacifist sentiments; it was the Party’s antiwar stand that won him over. Subsequently, the events of 1941—the German invasion of the U.S.S.R. and the attack on Pearl Harbor—were so flagrant he found his pacifism no longer tenable.

Trumbo, as almost everyone called him, was a tremendously appealing character, and I regarded it as a privilege to be his friend. Brought up in Grand Junction, Colorado, he had moved with his widowed mother to Los Angeles in the early years of the Depression. He worked in a bakery for a time, became a journalist, and published a novel (Eclipse) before breaking into the movie business as a reader and writer, and sixty dollars a week. Like Ben Hecht, he was renowned for his speed and had turned to the movies (and away from what he considered his more serious work as a novelist) in part to satisfy a large appetite for money; like Hecht too, he wrote some fine pictures, including Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (a war movie singularly free of the heroics and hokum that sometimes characterized the genre) and Our Vines Have Tender Grapes, a story of farm life that, in its low-keyed simplicity, represented the direction in which many of us hoped to see Hollywood go after the war. By 1946, Trumbo’s salary was three thousand dollars a week or seventy-five thousand a script, whichever he chose. Either way, he spent every bit of it, largely on improvements and additions to a dilapidated house he had purchased in the remote and inaccessible wilds of Ventura County. When the blacklist hit, Trumbo was forced to sell the place, and he had to do masses of undercover work at vastly lower prices just to get by. When he returned to the top rank of Hollywood writers in the 1960s, he also returned to his grandiose spending habits.

The Party, the Screen Writers Guild, and the various Hollywood organizations devoted to the fight against fascism became the anchors of our social life in the prewar years; and when the guild won its battle against the Screen Playwrights, some of us served as missionaries or consultants to other categories of movie workers. I was assigned, for example, to advise a group at Warner Brothers who were trying to form a readers’ guild. That was how I met Alice Goldberg, the extremely bright and attractive daughter of a Russian-born photographer—and how she met Ian Hunter. He was still boarding with Silvia and me, having moved with us from an apartment on Vista Del Mar to a house on Franklin Avenue, formerly occupied by Bette Davis.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31939)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31928)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26592)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17402)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15935)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15328)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13885)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13315)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12368)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8968)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8913)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7663)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7557)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7320)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6194)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5412)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5371)