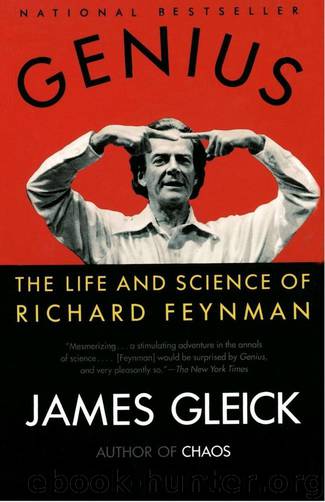

Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman by James Gleick

Author:James Gleick

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub, azw3

Tags: Science, 20th century, General, United States, Physicists, Biography & Autobiography, Physics, Science & Technology, Biography, History

ISBN: 9780679408369

Publisher: Pantheon Books

Published: 1992-04-14T21:00:00+00:00

Dyson Graphs, Feynman Diagrams

It was the affair of Case and Slotnick at the same January meeting that brought home to Feynman the full power of his machinery. He heard a buzz in the corridor after an early session. Apparently Oppenheimer had devastated a physicist named Murray Slotnick, who had presented a paper on meson dynamics. A new set of particles, a new set of fields: would the new renormalization methods apply? With physicists looking inward to the higher-energy particles implicated in the forces binding the nucleus, meson theories were now rising to the fore. The flora and fauna of meson theories did seem to resemble quantum electrodynamics, but there were important differences—chief among them: the counterpart of the photon was the meson, but mesons had mass. Feynman had not learned any of the language or the special techniques of this fast-growing field. Experiments were delivering data on the scattering of electrons by neutrons. Infinities again seemed to plague many plausible theories. Slotnick investigated two species of theory, one with “pseudoscalar coupling” and one with “pseudovector coupling.” The first gave finite answers; the second diverged to infinity.

So Slotnick reported. When he finished Oppenheimer rose and asked, “What about Case’s theorem?”

Slotnick had never heard of Case’s theorem—and could not have, since Kenneth Case, a postdoctoral fellow at Oppenheimer’s institute, had not yet publicized it. As Oppenheimer now revealed, Case’s theorem proved that the two types of coupling would have to give the same result. Case was going to demonstrate this the next day. For Slotnick, the assault was unanswerable.

Feynman had not studied meson theories, but he scrambled for a briefing and went back to his hotel room to begin calculating. No, the two couplings were not the same. The next morning he buttonholed Slotnick to check his answer. Slotnick was nonplussed. He had just spent six intensive months on this calculation; what was Feynman talking about? Feynman took out a piece of paper with a formula written on it.

“What’s that Q in there?” Slotnick asked.

Feynman said that was the momentum transfer, a quantity that varied according to how widely the electron was deflected.

Another shock for Slotnick: here was a complication that he had not dared to confront in a half-year of work. The special case of no deflection had been challenge enough.

This was no problem, Feynman said. He set Q equal to zero, simplified his equation, and found that indeed his night’s work agreed with Slotnick. He tried not to gloat, but he was afire. He had completed in hours a superior version of a calculation on which another physicist had staked a major piece of his career. He knew he now had to publish. He possessed a crossbow in a world of sticks and clubs.

He went off to Case’s lecture. At the end he leapt up with the question he had ready: “What about Slotnick’s calculation?”

Schwinger, meanwhile, found the spotlight sliding away. Dyson’s paper carried a sting—Dyson, who had seemed such an eager student the summer before. Now this strange wave of Dyson-Feynman publicity.

Download

Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman by James Gleick.epub

Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman by James Gleick.azw3

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(8369)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(7304)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7292)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6357)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(6162)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4255)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(4211)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4087)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4069)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3945)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(3868)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3850)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(3705)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3606)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3550)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(3477)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3466)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(3352)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(3319)