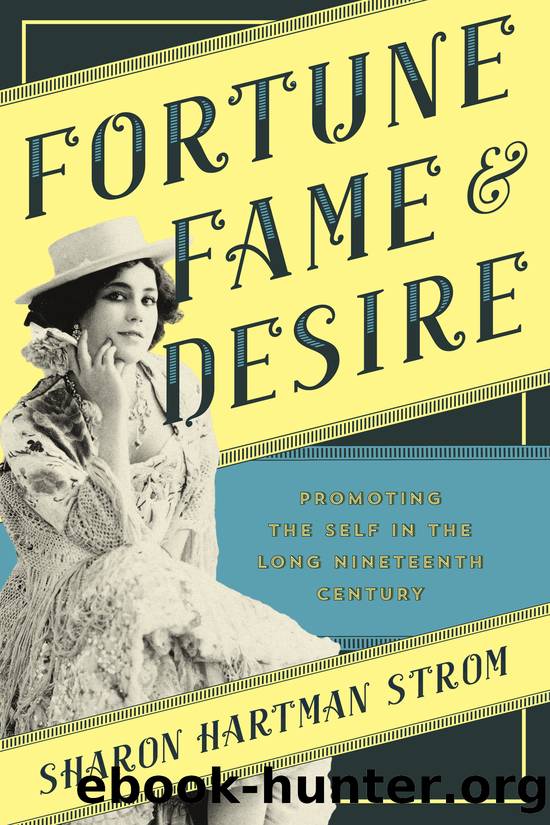

Fortune, Fame, and Desire by Strom Sharon Hartman;

Author:Strom, Sharon Hartman;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Unlimited Model

Chapter 5

âSelf Reliance,â âUniversal Redemption,â and âThe Obsessed Womanâ

Warren Chase, Joseph Osgood Barrett, and Juliet Stillman Severence

As black and white Americans sought new ways to earn livings and promote their public reputations, some turned to philosophical and religious movements that were challenging Protestant orthodoxy to expand their ambitions. Between 1790 and 1830 the Second Great Awakening spawned enthusiasticâand competingâchurches throughout the United States. Mother Ann Leeâs Shakers, Elias Hicksâs Quakers, William Millerâs second coming followers, Joseph Smithâs Latter Day Saints, and self-proclaimed African American ministers, some of them women, experimented with radical challenges to the traditional white and male-dominated clergy. The mainstream churchesâCongregationalists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, and African Methodist Episcopaliansâall stressed the critical juncture of coming to Christ, being born again, and applying Godâs word from the holy text of the Bible to everyday life. Many white and black Americansâlike Frances Watkins Harperâcontinued to immerse themselves in this worldview.

The decades surrounding the American Revolution also saw the emergence of what many perceived to be a more modern and rational path. The Enlightenmentâthe transatlantic values of Deism, Liberalism, and rational inquiry that underpinned the French and American Revolutionsâwas often endorsed by the more educated and adventurous, like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. The language of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution reflected the centrality of the Enlightenment in the foundersâ consciousness, with its stress on the separation of church and state, the universality of human rights, full citizenship for white men, and faith in the possibility of social progress.

John Murray, an Anglican convert to Wesleyan Methodism, left London for America in 1770 and challenged predestination by preaching what he called âuniversal redemption.â Jesus Christ, Godâs link to man on earth, died so that all would be saved. The point of sermons was to convince congregants of Godâs possible love and to stimulate good works by inspiration, not by chastisement or threats of damnation. The Scriptures were but one revelation of the character of God, not to be read literally. The Universalists created societies and meeting places from Maine to New Jersey but avoided the building of churches or overarching bureaucracies. Mirroring the egalitarian ethos of current day politics, Universalist groups were managed by their members and not only discussed religion but philosophy and science as well. Generals Nathaniel Greene and George Washington heard John Murray preach at Jamaica Plain during the Battle of Bunker Hill and appointed him the Continental Army Chaplin.1

Rationalist, âfree thinkingâ ideas were in the air, developing alongside Universalism and eventually calling even that Liberal view of Christianity into question. Thomas Paineâs radical work, The Age of Reason, encouraged some Americans to abandon traditional religion and seek a scientific approach to evidence and belief that bordered on agnosticism and even atheism. The Boston Investigator was founded in 1831 as an alternative to the stream of Protestant propaganda flooding the reading public. The Investigatorâs editor, Abner Kneeland, went from the Baptists to the Universalists and then to Free Thought, arguing that the existence of a Christian God who heard the prayers of churchgoers was wishful thinking.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Vikings: Conquering England, France, and Ireland by Wernick Robert(81309)

Ali Pasha, Lion of Ioannina by Eugenia Russell & Eugenia Russell(40237)

The Conquerors (The Winning of America Series Book 3) by Eckert Allan W(37379)

The Vikings: Discoverers of a New World by Wernick Robert(36964)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32538)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23069)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19025)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18564)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15324)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14476)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14358)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13340)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13332)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13306)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12363)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12081)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12012)