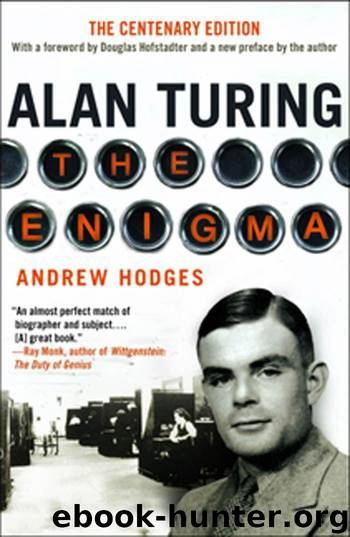

Alan Turing: The Enigma The Centenary Edition by Hodges Andrew

Author:Hodges, Andrew [Hodges, Andrew]

Language: eng

Format: azw3, epub, mobi

ISBN: 9780691155647

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2012-05-26T16:00:00+00:00

That was not how the world was to see it, and the world was not being entirely unfair. Alan Turing’s invention had to take its place in an historical context, in which he was neither the first to think about constructing universal machines, nor the only one to arrive in 1945 at an electronic version of the universal machine of Computable Numbers.

There were, of course, all manner of thought-saving machines in existence, going back to the invention of the abacus. Broadly these could be classed into two categories, ‘analogue’ and ‘digital’. The two machines on which Alan worked just before the war were examples of each kind. The zeta-function machine depended on measuring the moment of a collection of rotating wheels. This physical quantity was to be the ‘analogue’ of the mathematical quantity being calculated. On the other hand, the binary multiplier had depended upon nothing but observations of ‘on’ and ‘off’. It was a machine not for measuring quantities, but for organising symbols. In practice, there might be both analogue and digital aspects to a machine. There was not a hard-and-fast distinction. The Bombe, for instance, certainly operated on symbols, and so was essentially ‘digital’, but its mode of operation depended upon the accurate physical motion of the rotors, and their analogy with the enciphering Enigma. Even counting on one’s fingers, by definition ‘digital’, would have an aspect of physical analogy with the objects being counted. However, there was a practical consideration which provided the effective distinction between an analogue and a digital approach. It was the question of what happened when increased accuracy was sought.

His projected zeta-function machine would have well illustrated the point. It was designed to calculate the zeta-function to within a certain accuracy of measurement. If he had then found that this accuracy was insufficient for his purpose of investigating the Riemann Hypothesis, and needed another decimal place, then it would have meant a complete reengineering of the physical equipment – with much larger gear-wheels, or a much more delicate balance. Every successive increase in accuracy would demand new equipment. In contrast, if the values of the zeta-function were found by ‘digital’ methods – by pencil and paper and desk calculators – then an increase in accuracy might well entail a hundred times more work, but would not need any more physical apparatus. This limitation in physical accuracy was the problem with the pre-war ‘differential analysers’, which existed to set up analogies (in terms of electrical amplitudes) for certain systems of differential equations. It was this question which set up the great divide between ‘analogue’ and ‘digital’.

Alan was naturally drawn towards the ‘digital’ machine, because the Turing machines of Computable Numbers were precisely the abstract versions of such machines. His predisposition would have been reinforced by long experience with ‘digital’ problems in cryptanalysis – problems of which those working on numerical questions would be entirely ignorant, by virtue of the secrecy surrounding them. He was certainly not ignorant of analogue approaches to problem-solving. Apart from the zeta-function machine, the Delilah had an important ‘analogue’ aspect.

Download

Alan Turing: The Enigma The Centenary Edition by Hodges Andrew.epub

Alan Turing: The Enigma The Centenary Edition by Hodges Andrew.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9141)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(8451)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7892)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7857)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6945)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(5274)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4974)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4966)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4931)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(4790)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4746)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4593)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4482)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4360)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4329)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4212)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4140)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(4130)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3998)