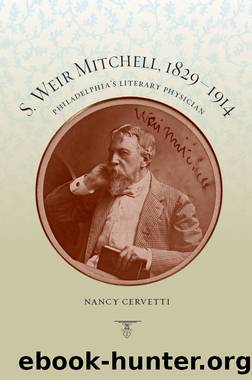

S. Weir Mitchell, 1829-1914 by Nancy Cervetti

Author:Nancy Cervetti [Cervetti Nancy]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of Wisconsin Press

Virginia Woolf was a brilliant writer and a key figure in the twentieth-century modernist movement. Gilman and Addams, as reformers and feminists, played major roles in creating new theory and praxis. Mason, a wealthy woman who never had children, was a critic and socialite. Wister was an essayist and âhomemaker,â but her home was an eighty-two-acre estate called Butler Place, and she was Mitchellâs cousin, someone he referred to as his âkinswoman.â Making generalizations about the rest cure based on a small number of women remains problematic, yet one common element does emerge: intelligent and articulate, these women needed and relentlessly pursued avenues of self-expression and transformation.

As a literary physician, Mitchell understood the value of voice and self-expression as well or better than anyone did. He viewed language use as immensely important and repeatedly recorded a personal need to write; he understood in conscious and explicit ways the personal, social, and professional consequences of having a strong voice and an education. Many of his female patients possessed the same need, but they were stifled in domestic space, struggling to find meaningful outlets for their creativity and intelligence. Evelyn Ender writes that the impossibility of verbal symbolization characteristic of the hysterical patient begins with her inscription into a tradition that relentlessly denies to women the ability to move from impressions to the realm of thought and language. Hysteria is âa vivid reminder of the fact that, for certain categories of subjects, consciousness remains secret not because of a choice but as an imposed condition.â76

At the age of fifty-nine, Virginia Woolf was hearing voices again. Her husband, Leonard, took her to Brighton to see Dr. Octavia Wilberforce. When Wil berforce asked her to undress for an examination, Woolf responded, âWill you promise, if I do this, not to order me a rest cure?â Wilberforce responded that when she had had this trouble before, she had been helped by a rest cure, and that should give her some confidence.77 Even then, in 1941, Mitchellâs rest cure was the most suitable treatment available to Woolf. But her great fear was that she could no longer write, and the day after this consultation she drowned herself in the River Ouse. While there were complex reasons for the suicide, Woolf âs writing was of the utmost importance to her. Judith Fetterley argues that the âstruggle for control of textuality is nothing less than the struggle for control over the definition of reality and hence over the definition of sanity and madness.â78 In the sexist culture of the nineteenth century, the stories that doctors and women told were not merely alternate versions of reality; rather, they were incompatible and could not coexist. An âexile from languageâ could be devastating. It denied womenâs intellect and substituted instead the social imperative called âduty.â79 When Mitchell restored womenâs bodies but denied their minds, he contradicted his own theory of the mind and body as one. Unable to recognize the great differences among women as a group, he judged all women according to a single type, and criticized and sometimes harmed those who did not fit his ideal.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Vikings: Conquering England, France, and Ireland by Wernick Robert(80456)

Ali Pasha, Lion of Ioannina by Eugenia Russell & Eugenia Russell(40228)

The Conquerors (The Winning of America Series Book 3) by Eckert Allan W(37378)

The Vikings: Discoverers of a New World by Wernick Robert(36964)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32533)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31931)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31923)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23065)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19012)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18561)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15316)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14473)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14355)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13338)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13327)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13302)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12360)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12080)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12009)