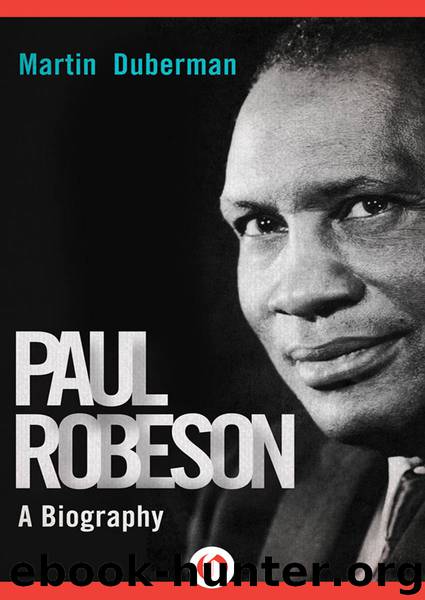

Paul Robeson by Martin Duberman

Author:Martin Duberman

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781497635364

Publisher: Open Road Media

CHAPTER 22

Resurgence

(1957–1958)

The enforced inactivity in Robeson’s life coincided, ironically, with an upsurge of movement for black Americans in general. The beaching of a man who had spoken out for two decades against the paralyzing oppression of black life now stood in stark contrast to the quickened hope that swept black communities across the nation. Not that the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown decision had in itself marked the swift demise of Jim Crow. Far from it. The court’s own implementing decision rejected the notion of rapid desegregation in favor of a “go-slow” approach, which itself proved too radical a notion for President Eisenhower; initially he refused to endorse the Brown ruling, remarking, “I don’t believe you can change the hearts of men with laws or decisions,” and calling his own appointment of Earl Warren to the Supreme Court “the biggest damn fool mistake I ever made.”1

The caution of official Washington was matched on the state level by fierce white resistance. On March 12, 1956, 101 Southern members of Congress issued a “Declaration of Constitutional Principles,” which called on their states to refuse implementation of the desegregation order. Defiance became the watchword in the white South, massive resistance the proof of regional loyalty. Every item in the white-supremacist bag of tricks—from “pupil-placement” laws to outright violence—was utilized to forestall integration of the schools. The Ku Klux Klan donned its masks and hoods; the respectable middle class enrolled in White Citizens’ Councils; the press and pulpit resounded with calls to protect the safety of the white race. A tide of hatred and vigilantism swept over the South. Some blacks knuckled under in fear; many more dug in, prepared once again to endure—and this time overcome. On December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks, a forty-two-year-old black seamstress, stubbornly refused to give up her bus seat to a white man—thereby launching the Montgomery bus boycott, energizing black resistance, catapulting Martin Luther King, Jr., and his strategy of nonviolent direct action to the forefront of the movement. An epoch of black insurgency had been ushered in.

Robeson, of course, applauded it—but from the sidelines, where he had been shunted. Confined by the white ruling elite, ostracized by the black establishment, he and his influence had been effectively neutralized. His limited access to the media, in combination with his disinclination to write, meant that he had few public opportunities to express his support for the burgeoning civil-rights movement. When one did present itself in July 1957, during a rare series of engagements in California, he told the press that he “urged the Negro people to support Reverend Martin Luther King—the strength of the Negro people lies within their organizations and churches, as demonstrated by the magnificent Montgomery, Alabama Bus Boycott and other activities conducted by the Negro people in the South.” And in September 1957, when the National Guard in Little Rock, Arkansas, under orders from Governor Orval Faubus, prevented nine black students from enrolling in Central High, Robeson issued a statement calling for a national conference to challenge “every expression of white supremacy.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Actors & Entertainers | Artists, Architects & Photographers |

| Authors | Composers & Musicians |

| Dancers | Movie Directors |

| Television Performers | Theatre |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31929)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31916)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26583)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19020)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17393)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15895)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15307)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14039)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13829)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13292)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12354)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8951)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8904)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7657)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7539)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7302)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6187)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5394)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5360)