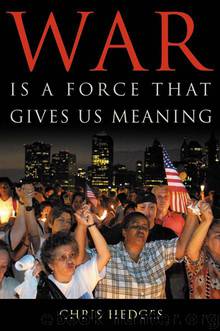

War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning by Chris Hedges

Author:Chris Hedges

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

ISBN: 1586480499

Publisher: PublicAffairs

Published: 2012-02-14T20:03:12+00:00

5

THE HIJACKING AND RECOVERY OF MEMORY

Our people’s lives pass, bitter and empty, among malicious, vengeful thoughts and periodic revolts. To anything else, they are insensitive and inaccessible. One sometimes wonders whether the spirit of the majority of the Balkan peoples has not been forever poisoned and that, perhaps, they will never again be able to do anything other than suffer violence, or inflict it.

•

IVO ANDRIĆ

Conversation with Goya: Signs, Bridges

HAGOB H. ASADOURIAN, LIKE MANY SURVIVORS OF genocide, communes with shadows. Some are dark and frightening, like the shades of Turkish soldiers, who in 1915 herded him and his family from his Armenian village, leaving him to watch his mother and four of his sisters die of typhus in the Syrian desert. Some are sweet, revolving around the raucous Armenian-language plays performed in the 1920s at the Yiddish Theater at Madison Avenue and Twenty-seventh Street in Manhattan. And some are poignant, like the reunion with his sole surviving sister, thirty-nine years after they lost each other one night near the Dead Sea as they fled with a ragged band of Armenian orphans from Syria to Jerusalem.

But his battle to preserve memory, the theme of his fourteen books, did not save him or his generation from the destructive march of time. And time, to the rapidly vanishing community of exiled Armenians, will soon finish the work that, he says, was begun by the Turkish army more than eighty-five years ago.

The Turks have spent most of the past century denying, with rather startling success, the Armenian genocide of 1915, when the Ottoman Empire, fearing a nationalist revolt, forced two million Armenians into the Syrian desert to die. The few surviving Armenians no longer ask to go home. They do not ask for restitution. They ask simply to have the memory of their obliteration acknowledged. It is a moral obsession, the lonely legacy passed onto the third and fourth generation who no longer speak Armenian but who carry within them the seeds of resentment that will not be quashed.

Asadourian’s latest book, The Smoldering Generation, was, he said, “about the inevitable loss of our culture.”

“No one takes the place of those who are gone,” the ninety-seven-year-old writer said when I visited him at his home in Tenafly, New Jersey. He was seated in front of a picture window that looked out on a carefully groomed garden. “Your children do not understand you in this country. You cannot blame them.”

As he spoke, his middle-aged son, John, who has used a wheelchair since a stroke, jerked himself into position behind his father. He listened, his head cocked slightly to one side, with a grimace.

Although there were once ten major Armenian-language daily newspapers in the United States, there is just one left, published in California. Armenian clubs have closed, social societies have been disbanded, and cultural events have dwindled. Proceedings of Armenian meetings, when they take place, are usually in English (except at church affairs, where Armenian clergy nearly always speak in Armenian first, then English). Asadourian said that he had accepted that his writing would not halt the slide to obliteration of the language.

Download

War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning by Chris Hedges.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31335)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30935)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30891)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21355)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18075)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13111)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12934)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12754)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12451)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11886)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11881)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8352)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7836)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6474)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6407)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5771)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5511)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5039)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4871)