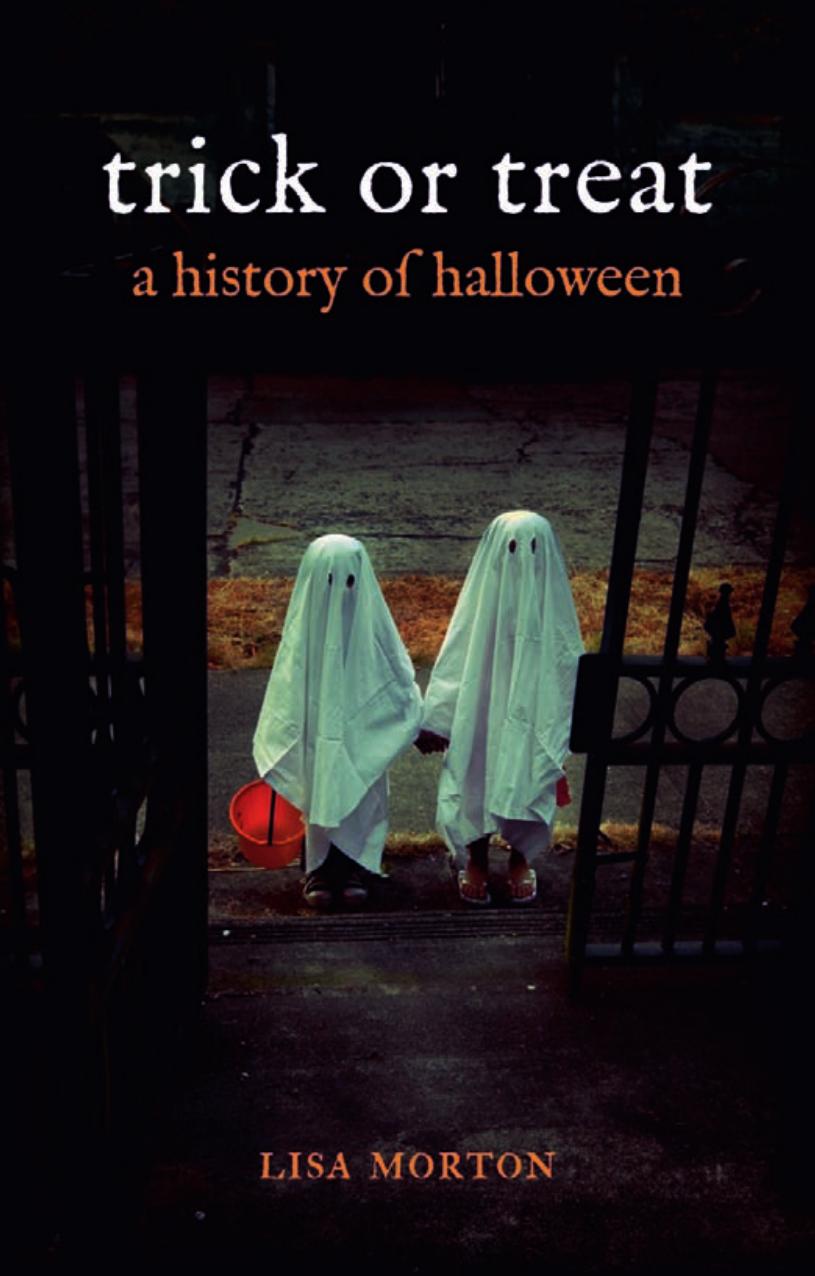

Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween by Lisa Morton

Author:Lisa Morton [Morton, Lisa]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi, pdf

Tags: History, Non-Fiction, Sociology

ISBN: 9781780231877

Amazon: 1780231873

Barnesnoble: 1780231873

Goodreads: 15108967

Publisher: Reaktion Books

Published: 2012-10-15T07:00:00+00:00

Culture Clash in Europe

The region of Europe in which 1 and 2 November most closely resemble the English-speaking Halloween prior to its arrival in America is Brittany, the large peninsula to the northwest of France. This is not entirely surprising, since Brittany is considered (along with Cornwall, Ireland, Scotland, Wales and the Isle of Man) to be one of the six Celtic Nations. Breton, still spoken throughout much of the area, is a Celtic language that shares its origin with the Welsh and Cornish tongues, and although the folklore of the region contains no references to Samhain – celebration that was probably confined to the Irish Celts – there is none the less a wealth of eerie, ghostly beliefs centred on All Saints’ and (especially) All Souls’ Days. Around 1900, travel authors were still referring to Brittany as ‘medieval’, and the Bretons believed that the dead returned on Le Jour des morts. Fishermen at sea on All Souls’ Eve risked having their boats invaded by the spirits of those who had drowned, now seeking passage back to land for a proper burial. Those on shore this evening might hear the voices of loved ones who had drowned, begging for prayers to be said in their names. In the Carnac area of Brittany,

peasants . . . believe that on the night of All Souls’ the church is lighted by supernatural means, and in the graveyard the graves give forth the dead, who wend their way along the road, to a church, where Death in the pulpit preaches a wordless, soundless sermon to a vast gathering of kneeling skeletons.6

Throughout most of Brittany, All Saints’ Day was for sombre remembrance of the dead, who were thought to return at midnight. During the day families prayed in church, where ‘Black Vespers’ (prayers made around a catafalque draped in black) were observed as per the Catholic Roman Rite. After the service, the entire parish then visited graveyards, where the priest blessed the graves. In the evenings, they placed food and drink – traditional pancakes and cider – out for deceased loved ones, and fires were left burning in hearths so the dead could warm themselves (these were built around the kef-am-Anaon, or ‘the Log of the Dead’). Bretons retired early on All Saints’ Eve, and avoided leaving home, since the roads were filled with wandering spirits; however, if it was absolutely necessary to venture outside, any small work tool, even a thimble or a needle, carried in a pocket would provide protection against malicious spirits.

Graveyards were an important feature of life in old Brittany, and many featured lanternes des mort; these curious structures were tall (seven to ten meters) stone towers surmounted by a lantern. They were often built in French cemeteries during the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. In Brittany, the lanterns were kept burning throughout the night on All Souls’ Eve.

A classic Breton cautionary tale tells of Wilherm (or Yann) Postik, a true son of an eol kornek (the horned angel). Wilherm refused to attend church, and didn’t mourn when his mother, sister and wife all passed away.

Download

Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween by Lisa Morton.mobi

Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween by Lisa Morton.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31326)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30929)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30886)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21197)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18067)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13102)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12924)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12741)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12445)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11876)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11865)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8343)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7831)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6465)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6404)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5763)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5504)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5032)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4863)