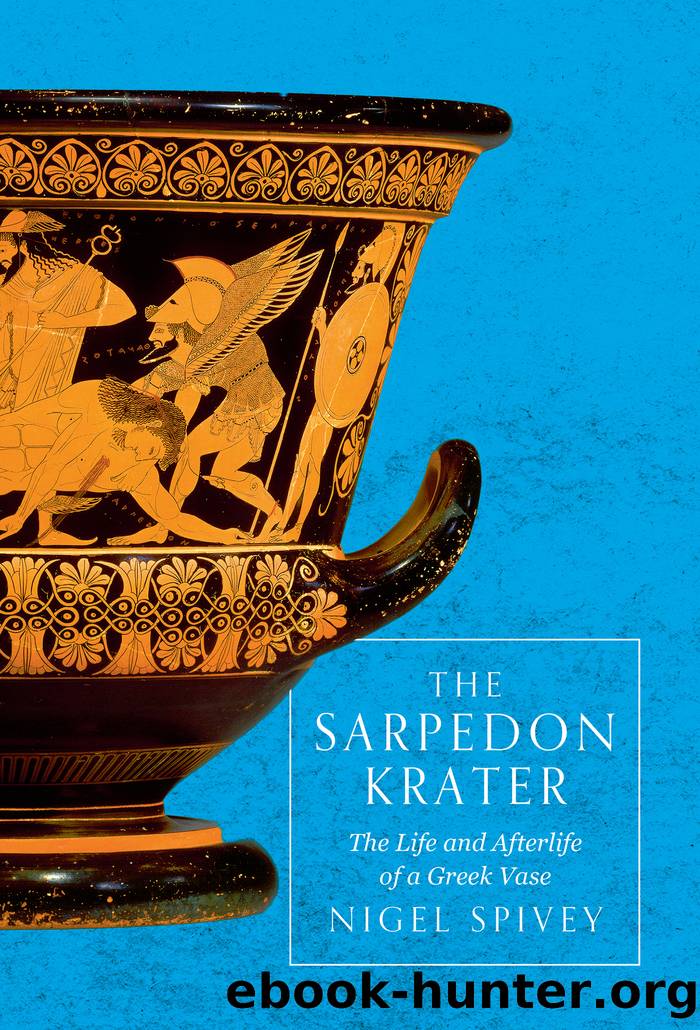

The Sarpedon Krater by Nigel Spivey

Author:Nigel Spivey [Spivey, Nigel]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781786691606

Publisher: Head of Zeus

Fig. 30 Detail of ‘the François Vase’, c.570 BC: Ajax (AIAS) carrying the body of Achilles (ACHIL[L]EUS, in retrograde). The full story of how Achilles died was told in the Aethiopis – one of the (mostly lost) poems of the archaic ‘Epic Cycle’. Florence, Archaeological Museum.

Fig. 31 Fragment of a calyx-krater attributed to Euphronios, c.515–510 BC. A poorly preserved kylix in the Getty Museum (77.AE.20) indicates that Euphronios tried the same subject earlier in his career, with a composition involving Achilles’ mother Thetis and his tutor, Phoenix. Here, just the last two letters of the name [AI]AS, ‘Ajax’, are visible. Approx. 15 cm (6 in) high. Formerly Princeton University Art Museum; now Rome, Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia.

Euphronios is unlikely to have seen this piece. But he took up the vignette of Ajax retrieving the fallen Achilles, on a vase that must have been of similar dimensions to the Sarpedon krater. Only minor fragments survive, yet one of these is enough not only to make an attribution to Euphronios, but also to envisage a significant portion of the decoration (Fig. 31). Ajax has the body of the bearded Achilles draped over his shoulders, in the manner of a fireman’s lift: supporting himself with his two spears, he kneels to pick up Achilles’ helmet with his free right hand, while retaining his shield. The impression that this is happening in the midst of combat is strengthened by parts of a figure striding forward, and of another sliding to his knees.

Repeatedly, Homer’s heroes either threaten to leave the bodies of their opponents as carrion for dogs and vultures, or else implore one another to be spared that horrible end. On the Sarpedon krater, we note that two senior warriors stand aside, as if respecting or guarding an act of pious decency. Their names are inscribed: to the left, LEODAMAS; to the right, in retrograde, HIPPOLYTOS. The former may connect to a ‘Laodamas, son of Antenor’, named as a Trojan victim of Ajax in fighting by the ships (Il. 15.516); interestingly, a post-Homeric author identifies this Laodamas as Lycian (Quintus Smyrnaeus 11.20–1). For the latter, it is suggested that Hippolochos, father of Glaucus, is intended. In either case, then, these would represent comrades or allies on Sarpedon’s side. But what of the other side of the vase? How do the figures there relate – if at all – to the image of our hero?

It has been suggested that we are wrong to think of the Sarpedon image as ‘heroizing’, and that it is rather the spectacle of ‘a desecrated or defiled corpse’, visually gratifying to Greeks because it shows the vanquished body of a non-Greek enemy, moreover visually gratifying to an Etruscan viewer because Etruria was where ‘such gory scenes were savoured’. There are several reasons why this proposal is unconvincing. To begin with, there is no forgetting that while Sarpedon, as a Lycian ally of the Trojans, is non-Greek, he is nonetheless a son of Zeus: as such, he could hardly be

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31331)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30933)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21264)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18072)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13107)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12929)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12746)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12448)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11880)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11874)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8347)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7833)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6469)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6405)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5767)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5510)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5034)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4868)