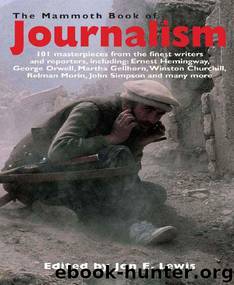

The Mammoth Book of Journalism by Lewis Jon E

Author:Lewis, Jon E. [Lewis, Jon E.]

Language: eng

Format: mobi, pdf

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

“The 1984 peak was followed

by a marked decline,” says

Postovalova,

“which

we

attribute to the recent anti-

alcohol campaign, since so

many suicides are committed

under the influence of drink. On

the other hand, the suicide rate

amongst adolescents and the

old has risen dramatically.

“Statistics fail to convey the

full picture. Let’s say there are

1,275 suicides in Moscow in

1987, 660 in Leningrad, and

210 in Izhevsk. Now it may

appear that things are very

much better in Izhevsk, but in

fact the situation is far more

alarming

there

than

in

Leningrad, where the rate is 15

per 100,000 of the population,

whereas in Izhevsk it’s as many

as 33 in every 100,000.

“Because the statistics have

been concealed for so long and

scientists haven’t had access to

them, there’s a lot that’s hard

to explain, and we have no

available data on people’s

social status, family situation,

ethnic origins, state of health,

or possible motivations for

killing themselves. Take the

1986 statistics for the Latvian

Republic, for instance, where

more than seventeen times

more twenty – to twenty-four-

year-old men commit suicide

than women. Women of the

same age in Tadjikistan in the

same year, however, are 1.6

times more likely than men to

commit suicide. Why is this? Or

consider Udmurtia, which leads

the autonomous republics with

41.1 suicides for every 100,000

of the population, almost the

same rate as in Hungary, which

has the highest suicide rate in

the world. But why Udmurtia?

Why

not

neighbouring

Mordovia, where the figures for

1986 were just 16.9?

“Then the suicide rate in the

countryside has now started to

exceed that in the towns. Why

is this? Which social groups are

most likely to commit suicide in

the cities? Only when we have

the full picture and can study it

as thoroughly as do our

Western counterparts can we

begin to give effective help to

those who need it.”

Lydia

Postovalova’s

Suicidology

Centre

is

attempting to find answers to

these and other questions. I

asked the Centre’s director,

Honoured Scientist of the USSR

Aina Ambrumova, to tell me

about its work.

“We’re the centre of a

complex

of

social

and

psychological welfare offices, a

telephone help-line, and the

Soviet Union’s first crisis clinic.

This clinic is very different from

the usual psychiatric hospital.

We try here to identify people

with suicidal tendencies, and to

work with those who have

already attempted suicide. We

have

already

had

some

success.

Repeated

suicide

attempts have sharply declined

in Moscow thanks to us, and all

the evidence points to the high

probability of these second

attempts, especially in the first

year.

“But we still have a lot of

problems. The telephone help-

line, for instance. For a long

time it was referred to very

grudgingly as a bourgeois

invention, of no possible use to

any Soviet citizen, so it’s hardly

surprising if not as many people

know about it as we would like.

It operates twenty-four hours a

day, seven days a week, and

we very much hope that

Moscow’s example will be

followed

by

other

towns,

especially

places

like

Sverdlovsk and Arkhangelsk,

where the situation is especially

worrying.

“But the clinic is our proudest

achievement.

People

in

psychological

distress

come

here voluntarily and talk to

experienced psychiatrists, and

they

leave

feeling

quite

different about things . . .”

The clinic is indeed very cosy,

with

comfortable

furniture,

discreet lighting, nice curtains,

and none of the doctors

wearing white coats. It has only

thirty beds, and when you

consider all the thousands of

people trying to kill themselves,

thirty beds does seem an

awfully small number, even

with

nice

curtains

and

comfortable furniture. But thank

goodness even for them.

It is seven o’clock. Psychiatrists

Poleev and have spent the day

teaching their patients to live,

and now their working day is

over and we sit talking over

glasses of tea.

“You think people commit

suicide because they don’t want

to live?” Alexander Poleev asks

me. “Nothing of the sort! Many

of them want to live more than

you or I.

Download

The Mammoth Book of Journalism by Lewis Jon E.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32562)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32023)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31959)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31945)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19052)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16050)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14522)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14172)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14081)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13376)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13376)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13247)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9347)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9297)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7509)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7316)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6770)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6626)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6284)