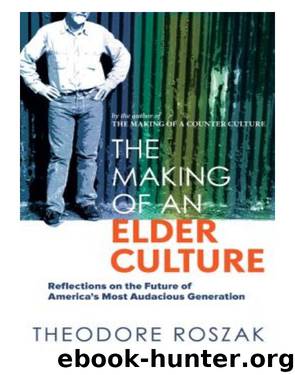

The Making of an Elder Culture by Theodore Roszak

Author:Theodore Roszak

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: New Society Publishers

Published: 2010-07-14T16:00:00+00:00

2. John Kenneth Galbraith’s Cyclically Graduated Compensation

There is something to be learned about the era of the Great Affluence by comparing Paul Goodman and John Kenneth Galbraith simply as personalities. Goodman was a voice from the countercultural margins of our society, the somewhat screwy man of letters who wrote more about sex, art, and psychology than about economics and whose finest piece of writing (Empire City) was a novel, not a political treatise. He fancied himself a Socrates of the streets, more homoerotically at home with boys on the basketball court than with decision-makers in the corridors of power. It was just this maverick stance that allowed Goodman to cultivate an audience among young boomers of the 1960s. He offered himself to them in the school yards and on the campuses as a true elder. The fact that someone so offbeat could find a significant audience tells us much about the spirit of the times.

In contrast, Galbraith was every inch the professional economist and man of affairs, a Harvard professor who served as US ambassador to India. His style, lofty and elegantly mordant, dripped with respectability. Academically trained and practically oriented, he might, therefore, seem as remote from utopian philosophy as one can travel. It is all the more impressive, then, that so restrained a theorist shared so much common ground with Goodman. Both came to see that our high industrial economy had, in the aftermath of World War II, reached a point where the difference in degree — of output, profit, production, consumption — had become a difference in kind. The economy had not simply changed; it had mutated. Not only can we produce more, we can produce too much. Thinkers like these could recognize that even before the means of production had been automated.

In Goodman’s case, the inspiration for redesigning industrialism derived from anarchist ancestors reaching back to Prince Kropotkin and William Morris; Galbraith, working out from Keynesian–New Deal liberalism, reached the same conclusions about the abundance of our postwar economy. Indeed, his 1958 book, The Affluent Society, helped name the period. Like Goodman, Galbraith wrote with a sense of astonishment and hope at what he saw before him. Surveying the American scene from the vantage point of the Eisenhower era, he was amazed at the productive potential he saw, wealth that might well spell the end of poverty. He was among the first of those in the intellectual-academic mainstream to recognize that America’s expanding economy changed all the rules of the game.

Hitherto, he observed, economic thought had been based on “poverty, inequality, and economic peril.” That was the world of yesterday. “Poverty,” Galbraith reminded his readers, “was the all-pervasive fact of that world. Obviously it is not of ours.... So great has been the change that many of the desires of the individual are no longer even evident to him. They become so only as they are synthesized, elaborated, and nurtured by advertising and salesmanship.... Few people at the beginning of the nineteenth century needed an adman to tell them what they wanted.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31331)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30933)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21262)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18072)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13107)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12928)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12746)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12448)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11879)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11874)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8346)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7832)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6469)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6405)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5766)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5510)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5034)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4868)