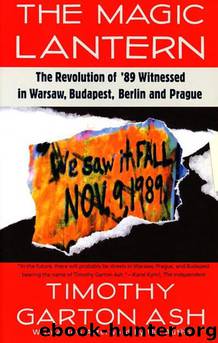

The Magic Lantern: The Revolution of '89 Witnessed in Warsaw, Budapest, Berlin, and Prague by Timothy Garton Ash

Author:Timothy Garton Ash [Ash, Timothy Garton]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, Europe, Eastern

ISBN: 9780679740483

Google: dbzeWhXpG3cC

Amazon: 0679740481

Publisher: Vintage

Published: 1993-08-29T16:00:00+00:00

Behind everything there was the benign presence of Gorbachev's Soviet Union: the Soviet embassy in Prague receiving a Forum delegation with ostentatious courtesy, Gorbachev himself giving marching orders to Party leader Urbánek and Prime Minister Adamec during the Warsaw Pact post-Malta briefing in Moscow, the renunciation of the 1968 invasion. Others will have to assess how far (and how) Gorbachev deliberately pushed the changes in Czechoslovakia, and to what extent this was affected by his personal timetable of East-West relations, particularly in the runup to the Malta summit. Just as in 1980 the very worst place from which to assess the Soviet intention to invade was the Solidarity headquarters in Warsaw (a point never entirely grasped by television and radio interviewers) so in 1989 the worst place from which to assess the Soviet intention to do the opposite of invading was the Forum headquarters in Prague. Yet, of course, in a larger historical frame the Soviet attitude was fundamental.

At this point the 'powers that be1 shade into the third force, or theatre, called 'the world'. The first protesters in Prague on the national anniversaries in 1988 chanted at the riot police: 'The world sees you.' Yet in the autumn of 1988 it was, in fact, very doubtful if the world did see them. On the whole, the world considered that life was elsewhere. But now there was absolutely no doubt that the world saw them. It saw them through the eyes of the television cameras and the thousands of foreign journalists who flocked into the Magic Lantern for the daily performance. They were a sight in themselves: television crews and photographers behaving like minotaurs, journalists shouting each other down and demanding to know why the revolution could not keep to their deadlines.

Yet a few of the questions were good, and the journalists served two useful functions. First, they concentrated minds. When there was a Forum plenum at, say, five p.m., the knowledge that their spokesmen would have to field the hardest questions at seven-thirty p.m. made for a much sharper discussion: although even then. Forum policy on crucial issues—the future of the Warsaw Pact, for example, or that of socialism—was sometimes made up on

the wing, in impromptu answers to Western journalists' questions. Secondly, the 'eyes of the world' offered protection. Particularly in the run-up to the Malta summit, the Czechoslovak authorities must have been left in little doubt that there were certain things that they could no longer do, or could only do at an immense price in both Western and Soviet disapproval. Beating children, for example. Both externally and internally, the crucial medium was television. In Europe at the end of the twentieth century all revolutions are telerevolutions.

Day Eight (Friday, 24 November). In the morning, a plenum in the smoking room. Appointing people to the commissions. The agenda for this afternoon's demonstration. The proposed slogans, someone says, are: 'Objectivity, truth, productivity, freedom'. It is no surprise that two out of four have to do with truth. But 'productivity' is interesting.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5105)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4808)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4770)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4350)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4204)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4104)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3997)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3975)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3430)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3361)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3330)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3208)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3196)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3153)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3119)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3081)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2935)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2930)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2857)