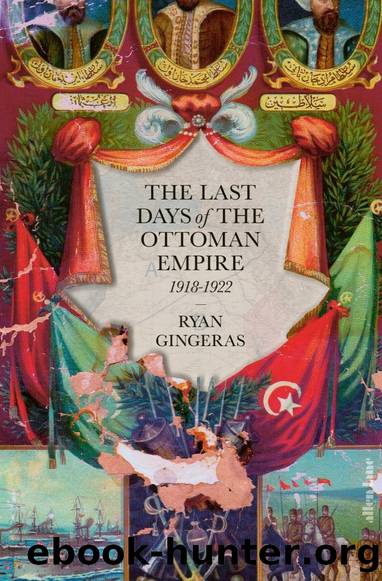

The Last Days of the Ottoman Empire: 1918-1922 by Ryan Gingeras

Author:Ryan Gingeras [Gingeras, Ryan]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780141992785

Google: kSVhEAAAQBAJ

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 60229100

Publisher: Penguin Random House UK

Published: 2021-12-02T00:00:00+00:00

âBRIGHTEST JEWELS IN THE OTTOMAN CROWNâ: THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT AND THE FATE OF THE ARAB LANDS

In Damascus today, a wide boulevard known as an-Nasr runs west from the foot of the cityâs ancient citadel. On either side of the street lie two of the most important landmarks left in Syriaâs largest city by the Ottoman Empire. Just north of the street is Martyrsâ Square, which served as the administrative epicenter of Damascus after the late nineteenth century. To the south, at the far west end of the street, sits a disused railway station which once connected Damascus to Istanbul and to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. When it was first built, the boulevard was named after the military governor who oversaw its construction, Cemal Pasha. As commander of the imperial Fourth Army during the Great War, Cemal Pasha endorsed a series of infrastructure and renovation initiatives throughout the Levant. He constructed intercity highways and urban streets, widened roads, and beautified thoroughfares with trees and walkways. He supervised the opening of primary and secondary schools as well as mosques and religious endowments. With German help, he lent government support to the excavation and restoration of the regionâs antiquities. Expanding the protection of ancient sites, he declared, was critical, so that âno Ottoman patriot could fail to respect the artistic achievements of past civilizationsâ.68

One of Cemalâs wartime aides, Ali Fuad, did not necessarily see the governorâs dedication to public works in altruistic terms. The paving of Cemal Pasha Boulevard clearly served no military purpose. The same could be said for other efforts he endorsed, such as the building of parks, clubs and casinos in Beirut and other cities and towns. Such ventures, as Fuad put it, were âdecorative symbols of civilizationâ suitable only in peacetime.69 More than anything, they distracted from the perilous state of Cemalâs beleaguered administration. After a failed offensive against British-held Egypt, the Ottoman Fourth Army contended with the constant threat of Allied invasion from the coast. Famine devastated much of the countryside within the warâs first year. Conditions in Beirut were so hopeless, as another aide to Cemal Pasha put it, that the cityâs streets echoed with âthe moans of those in their death throes from hungerâ.70 Then there was the threat of popular insurrection, an anxiety that plagued senior officials through much of the war. By his own account, Cemal âfelt perfectly sure of the civil populationâ, never once sensing the need to question the loyalty of the Arab soldiers who defended the Levantine coast.71 His subordinates, however, later testified that this was not the case. By the closing stages of the war, Cemal and his staff saw to it that they were guarded by units comprising Sufi dervishes from Anatolia and volunteers from the Balkans, not Arabs. Their headquarters, in the words of Ali Fuad, was âlike an isolated island in a sea of revoltâ.72

The sentiments and actions of Cemal Pasha and his staff epitomize a paradox at the heart of the empireâs final years.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Bahrain | Egypt |

| Iran | Iraq |

| Israel & Palestine | Jordan |

| Kuwait | Lebanon |

| Oman | Qatar |

| Saudi Arabia | Syria |

| Turkey | United Arab Emirates |

| Yemen |

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22190)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4431)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4199)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4029)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3531)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3065)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2616)

The History of Jihad: From Muhammad to ISIS by Spencer Robert(2213)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2079)

The Turkish Psychedelic Explosion by Daniel Spicer(1997)

No Room for Small Dreams by Shimon Peres(1994)

Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad by Gordon Thomas(1956)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(1947)

The First Muslim The Story of Muhammad by Lesley Hazleton(1888)

Arabs by Eugene Rogan(1845)

Bus on Jaffa Road by Mike Kelly(1791)

Come, Tell Me How You Live by Mallowan Agatha Christie(1774)

Kabul 1841-42: Battle Story by Edmund Yorke(1653)

Citizen Strangers by Robinson Shira N.;(1539)