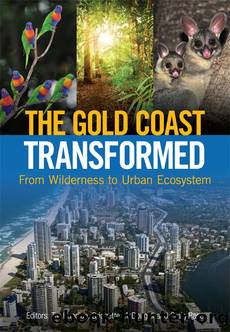

The Gold Coast Transformed by Hundloe Tor;McDougall Bridgette;Page Craig;

Author:Hundloe, Tor;McDougall, Bridgette;Page, Craig;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: CSIRO Publishing

Some hazards for urban wildlife

While possums may not be welcome houseguests, one animal group that is typically not tolerated at all is snakes. A surprising number of people hate them, and insist that âthe only good snake is a dead oneâ. People have an aversion to snakes because they are considered dangerous â and many are.

Australia does have some venomous snakes but not all of them can achieve purchase on anything larger than a finger or toe, and few attack unprovoked.2 Other than attempting to kill or handle a snake, the most dangerous encounter a human can have with one is when the animal is sluggish, having recently emerged from its shelter site after a cool period to thermoregulate.3 If startled while still sluggish, the snake may retaliate. Unfortunately for urban reptiles (including snakes), often the most efficient place to thermoregulate is in full sun on a tarred road surface. Consequently, many end up as roadkill, particularly in early spring when they emerge after spending the cooler months inactive. However, it is not only snakes that become such victims. Two reptile species that occur on the Gold Coast, the bearded dragon Pogona barbata and jacky lizard Amphibolurus muricatus, suffer the same fate. The most frequent victims appear to be the largest adults. Size does matter in reptiles; larger animals tend to lay more and larger eggs than smaller individuals. Loss of the larger animals from the population can therefore significantly impact on the populationâs viability (Hitchen et al. 2011). While writing this in early spring when reptiles typically emerge after winter inactivity, I observed a large eastern water dragon Physignathus lesueurii, coloured to attract a discerning female, on the edge of the Gold Coast Highway (M1), oblivious to the vehicles screaming by at 100 km/hr. I sincerely hope that he did not attempt to cross the highway in the peak hour traffic.

The Australian freshwater turtle, the long-necked turtle Chelodina longicollis, prefers terrestrial environments more than other Australian turtle species (Ryan and Burgin 2007). The species is native to the Gold Coast. While they spend much of their time in water, some individuals move among wetlands and may also bruminate (often assumed to be estivation but with physiological differences) on land. When migrating, these animals move in effectively a straight line: when a ânewâ obstacle (e.g. building, motorway) blocks their path, they proceed if possible. If the obstacle totally blocks their migration path they become confused. For example, I have intercepted the same turtle on three occasions over a period of five to six years; its migration path had been blocked by a building for â¼30 years. This turtle was (presumably) using that migration route before the building was erected.

Because they are slow-moving, migrating turtles are common victims of vehicle collision. A new motorway is particularly deadly, but the number of animals killed by vehicles soon dwindles â presumably because the turtles that use the migration route that requires them to cross the new roadway have been decimated.

Frogs are another taxon that is particularly vulnerable to vehicle collision.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(41993)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(33116)

Rewire Your Anxious Brain by Catherine M. Pittman(18643)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18235)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15334)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14367)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13315)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12651)

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Kahneman Daniel(12254)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12085)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12017)

The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli(10451)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9318)

A Journey Through Charms and Defence Against the Dark Arts (Harry Potter: A Journey Throughâ¦) by Pottermore Publishing(9269)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8363)

Wonder by R. J. Palacio(8097)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8040)

Change Your Questions, Change Your Life by Marilee Adams(7758)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7690)