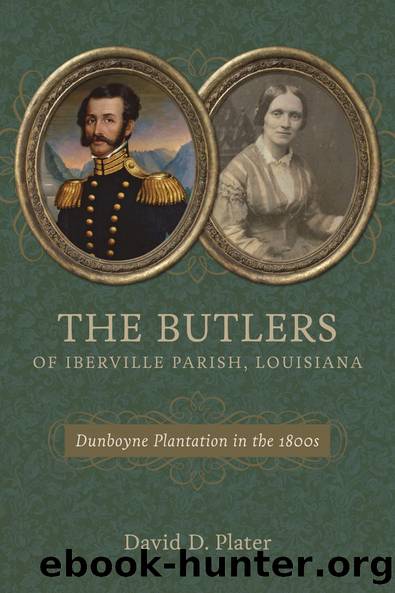

The Butlers of Iberville Parish, Louisiana by David D. Plater

Author:David D. Plater [Plater, David D.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, United States, State & Local, South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), Social Science, Regional Studies

ISBN: 9780807161296

Google: aiCMCgAAQBAJ

Publisher: LSU Press

Published: 2015-11-18T05:46:17+00:00

10

Hardships and Sorrows

Dunboyne Endings

Near the warâs end, in 1864 and 1865, Lawrence Butler again was an assistant adjutant general, this time to Brigadier General Marcus J. Wright. Wright gained notoriety after the Civil War when he assembled the records of Confederate officers for the future publication of The War of the Rebellion. As the conflict was ending, he commanded the District of West Tennessee-Northern Mississippi, based in Grenada, Mississippi. Wright probably knew Major Butler from their participation in the Battle of Belmont, in which Wright commanded the 154th Tennessee Infantry. After Leeâs surrender at Appomattox Court House in April, various Confederate forces engaged in the formalities of their own surrenders. On May 1, acting on Wrightâs behalf, Major Butler undertook his last wartime assignment. He delivered to Union Army major general C. C. Washburn in Memphis an armistice agreement between General Richard Taylor, Wrightâs superior, and Union Army major general Edward Canby. Washburn refused any arrangement other than the terms which Lee and Grant had agreed to and sent Butler back to his command. The surrender was accepted on May 5, in Citronelle, Alabama, and Butler, paroled as a prisoner of war on May 17, soon made it home. His safe return from that cruel and wasteful war must have been joyous. Lawrence now would have to pitch in and help his parents and sister. Looking over the old place, he surely wondered whether Dunboyne ever would recover its prosperity.1

On top of the state of deterioration brought by war, floods came. Although none directly affected Dunboyne, Iberville and surrounding parishes suffered extensively. The Mississippi River deluged the region in 1866, 1867, and 1868. The impacts fell hard upon the economy. Many freedmen and whites were destitute, even near starvation, and to survive they required repeated intervention by the U.S. Army. In May 1866, the army shipped 19,600 rations from New Orleans for the three adjoining parishes of Iberville, West Baton Rouge, and Pointe Coupée. The following April, numbers of planters were compelled to remove, by skiff, from their flooded homes in âinterior Iberville.â Most affected were the poor of both races. âSurrounded with water for three or four months and . . . scarcely able to get out of their houses for a month after the water goes down on account of the mud,â they endured âsickness and continued debility; as for cultivating anything it is utterly impossible.â In the spring of 1867, the Iberville Parish Police Jury sent Lawrence Butler, then a juror, to New Orleans to plead for rations again. The army shipped food and supplies multiple times during April, May, and June. Six thousand rations arrived in Iberville and West Baton Rouge, and an additional â16,020 Rations, for distribution to the destitute,â were provided in March 1868.2

The devastation to Louisianaâs sugar industry, its labor difficulties, and the lack of requisite capital to recover presented tremendous challenges. Conditions tested the survival abilities of everyone. Two years after the end of the Civil War, the Lafourche planter David Pugh articulated the general unhappiness of his class when he reported to his wife, Ellen.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32548)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31947)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31932)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31917)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19035)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15962)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14489)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14058)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13933)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13350)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13349)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13233)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9324)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9280)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7494)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7306)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6745)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6611)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6267)