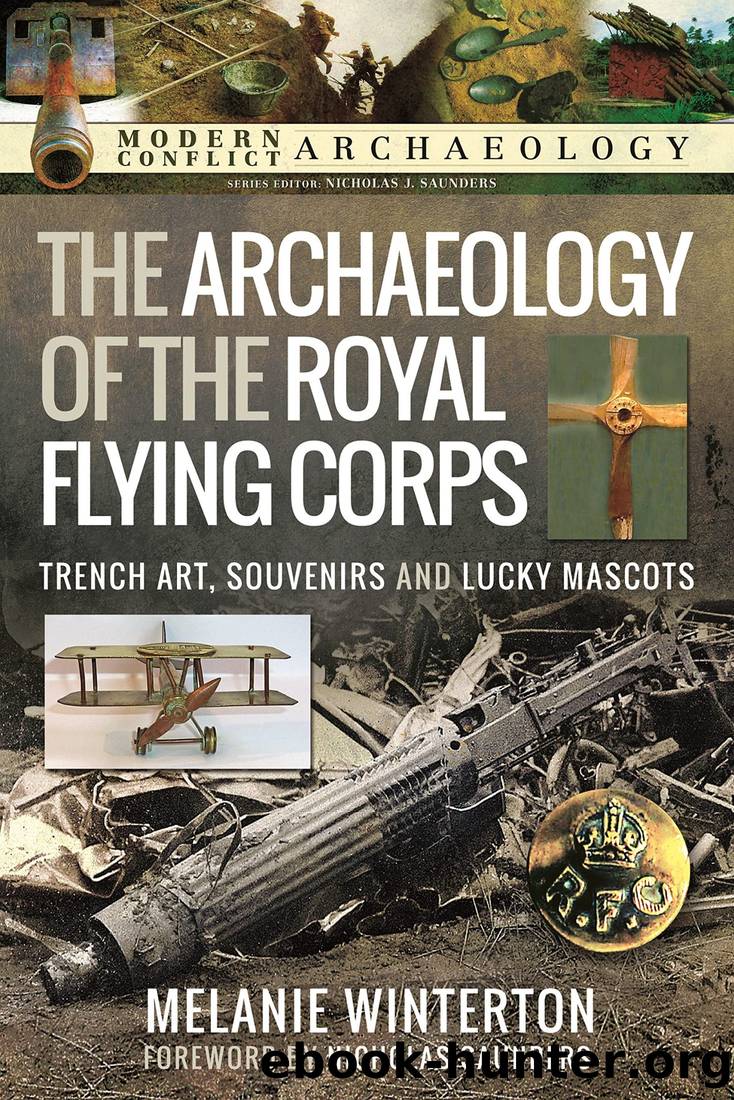

The Archaeology of the Royal Flying Corps: Trench Art, Souvenirs and Lucky Mascots by Melanie Winterton

Author:Melanie Winterton [Winterton, Melanie]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781399097260

Google: N2iIEAAAQBAJ

Publisher: Pen & Sword

Published: 2022-09-15T21:00:00+00:00

Chapter 8

Trench-art Propeller Grave Markers and the Stories they Tell

The following quotation is evocative of early aviation:

A mechanic swung the propeller and the engine coughed, fired and spluttered again; then someone behind me yelled âContactâ and the propeller melted into a blue mist in front of me.¹

Propellers of First World War aeroplanes were made from wood, often mahogany, and their unique shapes are characteristic of a period lasting about fifteen years, from December 1903 when the Wright brothers first flew at Kittyhawk, North Carolina, to the end of the First World War in November 1918.

In this chapter I investigate wooden aeroplane propellers retrieved from crashed aircraft and reworked into trench-art propeller grave markers for aviatorsâ graves. Pilot Duncan Grinnell-Milne observed, â[w]hereâs poor old P buried? We ought to stick a propeller-cross over his grave. A damn good fellow.â²

Taking a âbiographical approachâ this chapter identifies the events in the âsocial lifeâ of these distinctive objects through combing the literature to identify common events. Such markers may be considered âin terms of their involvement in the expression and the creation of emotional relationshipsâ and, since âemotions are culturally constructed ⦠they are amenable to archaeological [and anthropological] analysisâ.³ My aim is to reveal how the grave markers became imbued with pilotsâ flying experiences, and how new memorial spaces were created when these propellers were moved post-war to, for example, churchyards and private gardens. Adopting Hallam and Hockeyâs phrase âspatialised memoryâ, we see how these new spaces became powerful symbols of loss and memory and perhaps a living reminder of a loved one.â´

This aspect of my investigation reveals (and in some ways creates) ever closer relationships between anthropology and archaeology through its shared focus on material culture and on human-object interaction. Individual stories attached to âacquisition eventsâ â the appropriation of the propeller, usually removed from a crashed aeroplane â bestow significance on the commemorative legacies and give the deceased a powerful presence today.

Before the standardized Portland stone headstones of the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission were erected, graves were marked by simple wooden crosses bearing a metal plate with an identifying inscription or, in some instances, for aviators of the RFC, a propeller grave marker.âµ Very few of these have withstood the test of time and it is mainly photographic and textual evidence that attest to their existence.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(4156)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4143)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3894)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3680)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3569)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3491)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3303)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3108)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(2872)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(2787)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(2770)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(2710)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(2700)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(2680)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2636)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2498)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(2432)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2382)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2311)