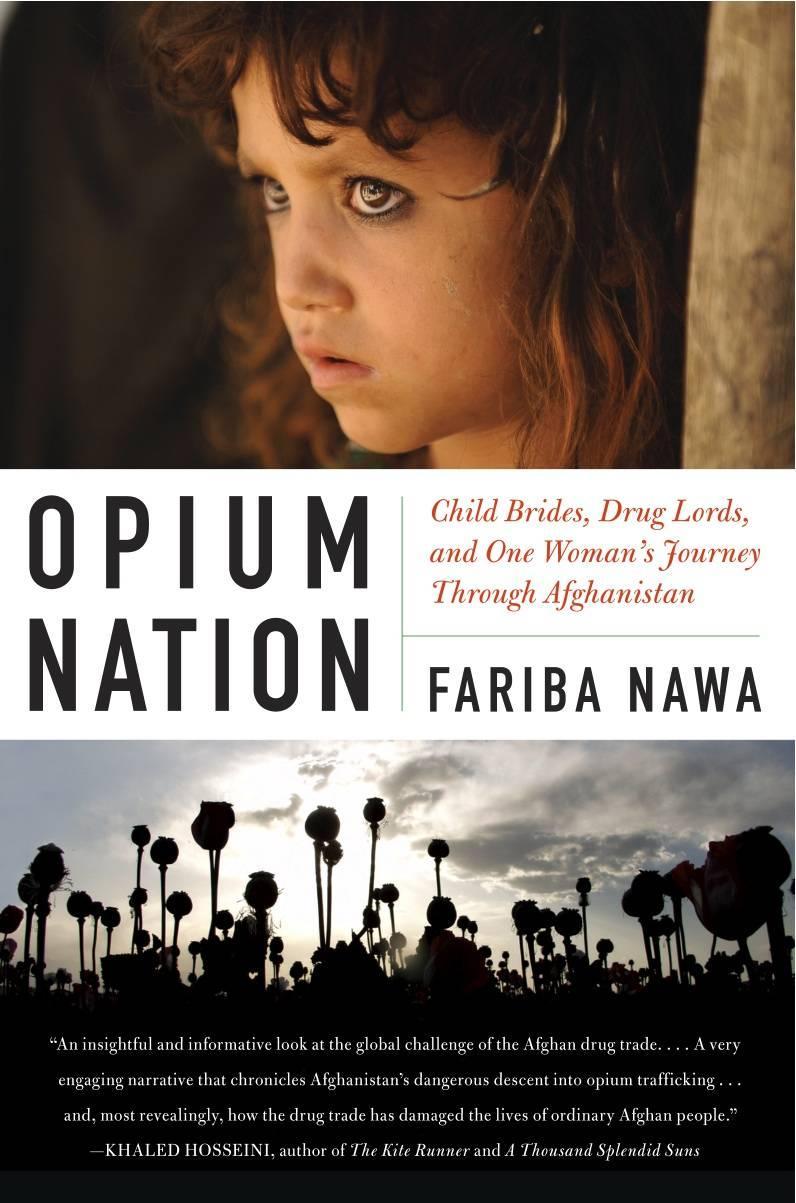

Opium Nation: Child Brides, Drug Lords, and One Woman's Journey Through Afghanistan by Fariba Nawa

Author:Fariba Nawa [Nawa, Fariba]

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2011-11-08T00:00:00+00:00

My father gave my mother the name Nafasgul, meaning “the breath of a flower,” as was tradition in their generation—husbands often gave their wives endearing nicknames when they first married. But my mother doesn’t like Nafasgul or her birth name, Sayed Begum. She’s a member of an Afghan elderly women’s group in Fremont, California, and the women there began calling her Saida, which in Arabic means the female descendant of the Prophet Mohammed. “I think it’s my right to change my name if I don’t like it,” she tells me. “Saida is much more meaningful than my other names.” Perhaps she’s right. After all, she does come from a Said family who traces their ancestry to the Prophet Mohammed. It’s one of my mother’s only attempts at asserting her independence.

Saida has spent her seventy-three years of life being a mother and wife, with a short stint teaching elementary school. The first time she saw my father was on their wedding night, when she was fifteen; their families arranged the marriage. She is a social butterfly who hates to miss a party, and her list of telephone numbers, all of which she has etched in her memory, is longer than my list of six hundred contacts. Saida is kind to a fault, putting others before herself, even when she shops; she keeps a chest full of gifts ready to hand out to friends and family for weddings, housewarmings, and birthdays. She tailors the gifts of clothing with her Singer sewing machine. Ever since I can remember, Saida has been ill, first with an incurable stomach ulcer, then with numerous sicknesses, including a slipped disc, which occurred when she immigrated to the United States. But her ailments have not dampened her desire to connect with others and to enjoy life. No matter how sick she is, Saida will dress up and put on a light coat of lipstick and foundation. She owns a small sterling silver container filled with black kohl, sorma, and a silver stick that she dips in the container and uses to draw a narrow line of black on the bottom lid of her cocoa-colored, doelike eyes. Her expensive head scarves are her signature fashion statement, to declare her piety and modesty. I have rarely seen my mother’s hair, except the gray bangs that neatly peek out. “My head becomes cold if I take off my scarf,” she admits to my father, giving him a gleaming white smile. She even sleeps with two layers of scarves on her head.

My clumsiness and disregard for fashion stand out when I’m with my mother. “Your mother is so beautiful and elegant,” people say, politely leaving out “What happened to you?”

Life in the United States has had its perks for Saida. She receives proper health care and has learned some words of English, which allowed her to pass her citizenship test. The clean water and food soothe her excessive need for cleanliness, and she no longer has to wear a burqa, as she did in her last years in Herat.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5762)

Autoboyography by Christina Lauren(5228)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4526)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4389)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4188)

Journeys Out of the Body by Robert Monroe(3617)

Annapurna by Maurice Herzog(3464)

Full Circle by Michael Palin(3443)

Schaum's Quick Guide to Writing Great Short Stories by Margaret Lucke(3375)

Elements of Style 2017 by Richard De A'Morelli(3343)

The Art of Dramatic Writing: Its Basis in the Creative Interpretation of Human Motives by Egri Lajos(3062)

Atlas Obscura by Joshua Foer(2955)

Why I Write by George Orwell(2945)

The Fight by Norman Mailer(2930)

The Diviners by Libba Bray(2927)

In Patagonia by Bruce Chatwin(2922)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2903)

Venice by Jan Morris(2568)

The Elements of Style by William Strunk and E. B. White(2470)