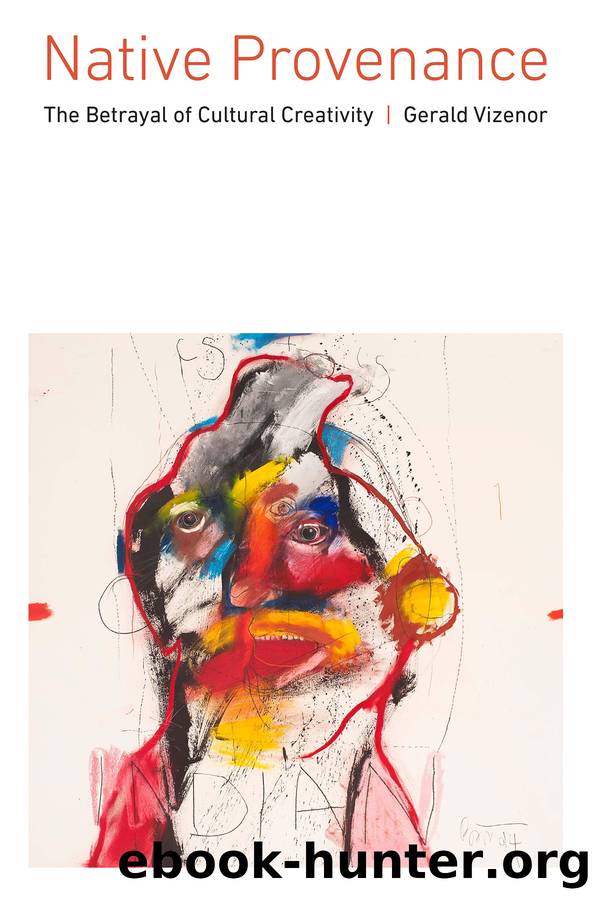

Native Provenance by Vizenor Gerald;

Author:Vizenor, Gerald; [Vizenor, Gerald]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: LIT004060 Literary Criticism / Native American, SOC021000 Social Science / Ethnic Studies / Native American Studies

Publisher: UNP - Nebraska

8

Native Nouveau Roman

Dead End Simulations of Tragic Victimry

The chase notes of discovery were easier to overcome with irony than the gossip theories of native cultures, the persistent and reductive reviews of natives in literature as romantic fades of victimry. The native stories of survivance are an unmistakable contrast, the visionary narratives of resistance and natural motion that create a sense of presence over monotheism, historical absence, cultural nihility, and victimry.1

Father Aloysius Hermanutz, Benedictine priest at the White Earth Reservation, “was constrained by holy black and white, the monastic and melancholy scenes and stories of the saints” in my historical novel Blue Ravens. “Black was an absence, austere and tragic. The blues were totemic and a rush of presence. The solemn chase of black has no tease or sentiment.” Black constrains natural motion and the “spirit of natives, the light and motion of shadows. Ravens are blue, the lush sheen of blues in a rainbow, and the transparent blues that shimmer on a spider web in the morning rain. Blues are ironic, and tease natural light. The night is blue not black.”2

God, “If You exist, make me blue.” Yes, “make me blue, fiery, lunar, hide me in the altar with the Torah! Do something, God, for our sake, for mine,” declared Marc Chagall in My Life, an early autobiography.3 Blue Chagall was a metaphor of natural motion and apparently was not intended to represent sadness or desolation; rather, he meant to be dreamy, an artistic, visionary presence, “make me blue.”

Chagall painted humans and other creatures blue, rabbis, fiddlers, and horses green, and some of the figures in his paintings were taller than houses, some standing on the roof of a house or soaring overhead, over his home village, Vitebsk, Russia, on the Pale of Settlement. These grand visionary scenes and creatures were represented and staged in a musical, then a popular movie by the same name, Fiddler on the Roof. The musical and motion picture depicted the dreams of the painter as commercial representations of religion and culture, a commercial product, in other words, and the transformation of a visionary image into a picture product that is easily recognized in popular culture. The Broadway musical production of Fiddler on the Roof was performed at least three thousand times more than forty years ago. The London production ran more than two thousand performances.

Today, anyone around the world could merely chant “tradition,” with a particular musical lilt, and most people would recognize the musical and motion picture, clearly a commercial representation of a dreamy, visionary painting of a rabbi playing a fiddle on a house in Vitebsk. The motion picture is a commercial simulation, of course, but wrongly a representation of culture or religion.

Chagall was never a commercial painter. He was an original, visionary artist, not a realist, not an artist of cultural representations. Yet sometimes, as in the musical and the movie, his wonderful dreamy, mythical green rabbis became commercial products, but, on the other hand, his painterly scenes were more accessible and visible, and to a much larger audience.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31331)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30933)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21262)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18072)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13107)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12928)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12746)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12448)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11879)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11874)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8346)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7832)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6469)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6405)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5766)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5510)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5034)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4868)