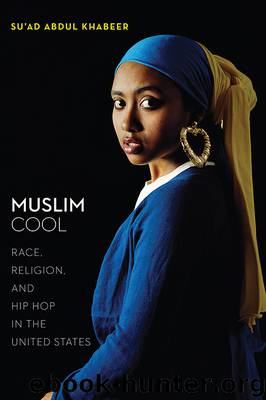

Muslim Cool by Su'ad Abdul Khabeer

Author:Su'ad Abdul Khabeer

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: SOC002000 Social Science / Anthropology / General

Publisher: NYU Press

It’s Complicated

Theorizing through the ’hoodjab, I hold that Muslim Cool is a technology of racial-religious performativity that constructs and “shores up” social identity. The ’hoodjab marked my teachers’ identities as Muslim women in the United States, underscoring the ways in which expressions of Muslim womanhood are implicated by ideas about Blackness. Blackness is central to the racial-religious performativity of the ’hoodjab and consequently to the process of self-making—the development of a sense of self and of belonging as a raced, gendered, and religious subject in the United States. As a “performance,” Muslim Cool reiterates the definition of race as a social construct that is formed and functions within contexts of power and inequality (Omi and Winant 1994; Gregory 1999; Hartigan 2005; Lipsitz 2006). Race is not a primordial essence, and its performance is something that must be learned and relearned.

Importantly, Muslim Cool’s privileging of Blackness is entangled in the epistemes of naming and valuation. In many ways, Noreen, Fatema, and Latifah as well as Noreen’s boss all identify the ’hoodjab as cool because it signifies hip hop, which in turn signifies Blackness, which is valued as the ultimate repository of cool in the United States. Further, as a material artifact of Black cool that is identified with Muslims, the ’hoodjab style makes the Muslim woman who wears it cool. The ’hoodjab thus loops through hip hop, Blackness, and Islam, and this loop is not without its problems.

When Blackness operates as a metonym for cool, the ’hoodjab can be a “site of negation.” For Noreen’s boss, the ’hoodjab was an emblem of the über-’hood narrative of Black life as poverty and pleasure, a story in which the complexities of place, class, and race become irrelevant. The ’hoodjab also exemplifies a negation of Black Muslim women. Academic narrations of Muslim women in hijab that overlook style presume that the Muslim women’s headscarf is worn only in ways that tie it to the Islamic East. This aesthetic elision is an erasure, albeit unintended, of U.S. Black Muslim women and their authorial imprint on the sartorial landscape of Islam in the United States.9 This erasure, then, is a reinscription of the ethnoreligious hegemony that Muslim Cool contests through embodied practices such as the ’hoodjab.

Indeed, representations and appropriations of Blackness are polysemous: Blackness holds a multiplicity of meanings. Blackness as cool is also a shorthand for righteous resistance to white supremacy as well as non-White hegemonies. The polysemous character of Blackness as cool holds potential for young Muslims doing Muslim Cool. For Latifah and Fatema the ’hoodjab was a technology of Muslim Cool that served as a conduit of self-making through racial sincerity. In this way, Muslim Cool highlights the links between race, gender, and religious subjectivity in the United States. Religious identity is not transcendent but rather is produced intersubjectively through complex racial pathways. Muslim Cool and its techniques of Blackness also reiterate race’s sincerity; it is unsettled and unsettling. Race is a tie that binds, in all the possible senses of the term.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31331)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30933)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21262)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18072)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13107)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12928)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12746)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12448)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11879)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11874)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8346)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7832)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6469)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6405)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5766)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5510)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5034)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4868)