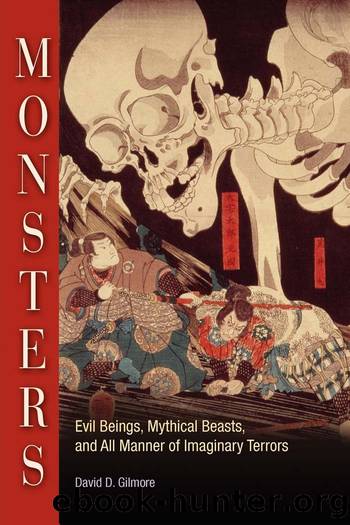

Monsters by David D. Gilmore

Author:David D. Gilmore

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780812203226

Publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc.

Kachina figure representing Awatovi Monster Man, painting by Cliff Bahnimptewa. Courtesy Heard Museum.

Monster Woman may be accompanied by Awatovi Soyok Taka, or Awatovi Monster Man. Like his female counterpart, he pretends to eat children.

Hopi artists have created a cottage industry of miniature Kachina dolls carved from wood and painted, as well as paintings. These are produced both for local use, as childrenâs toys, and for sale to visitors to the mesas.

MESO-AMERICAN MONSTERS

Crossing the border now into Mexico, we find monsters following hard on our heels. Early Spanish writers were impressed by the rich imaginary bestiary of the native Mexicans they conquered, especially the Aztec and Maya, whose pictorial art was more developed than that of their neighbors. Such luminaries as Bernardo de Sahagun and Bernal DÃaz del Castillo reported on such arcane matters in the fifteenth century, providing us with a glimpse into pre-Columbian monster legends. Other Spaniards detailed those of the Mayan peoples in the Yucatán and Guatemala. These notations are summarized in a book by Mexican folklorist Roldán Peniehe Barrera (1987), who provides us with a fascinating glimpse into native concepts of the demonic.

The Aztecs, for example, believed in all kinds of monstrous giant serpents. Aside from those mentioned earlier, one of these, the famous plumed giant Quetzalcoatl, was both monster and hero to them (Peniehe Barrera 1987: 135â36). Numerous lesser hybrids completed the Aztec imaginary bestiary. In their sacred book, the Chilan Balum, the Aztecs wrote about Hapai-Can, a great swallowing serpent (serpiente tragadora in Spanish), which sucks human blood and whose main diet is children. Another bloodcurdling beast was the ekuneil, or the great black snake. This was described as a monstrous serpentine creature like a huge anaconda that encircled and suffocated travelers. Still another was a two-headed giant python, which was said to have similarly violent propensities.

Not all Aztec monsters were serpentine in form. The Indians of central Mexico also feared numerous types of bipedal man-eating giants very similar in conception to those in Homerâs Odyssey and in other classical sources (Peniche Barrera 1987: 71â73). We have already mentioned Tlacahuepan, described as a humanoid ogre supposedly so big as to be able to hold a human in the palm of his hand. The terrified Indians made propitiation to this tyrant by sacrificing and butchering slaves captured from other tribes, whose free-flowing blood and still-palpitating hearts the monster greedily devoured. After scenting the blood, Tlacahuepan, like the giant in âJack and the Beanstalk,â lumbered forth to find his meal. Unless such gruesome sacrifices were made, the monster would eat any person who ventured too near (151â52).

Another terror was El Cráneo, the flying head. This was depicted in oral folklore as a large disembodied skull with chomping teeth that bit, tore, and swallowed humans. It was said to fly about at night, attacking people and animals. As in ancient Greece, not all pre-Columbian monsters were male. There was, for example, a ferocious water spirit whose native Aztec name, Chalchiuhicueye, translates as âshe who wears a skirt of emeraldsâ because she had an jewel-encrusted scorpionâs tail.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31332)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21264)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18072)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13107)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12929)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12746)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12449)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11882)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11875)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8348)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7833)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6469)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6405)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5767)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5510)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5034)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4868)