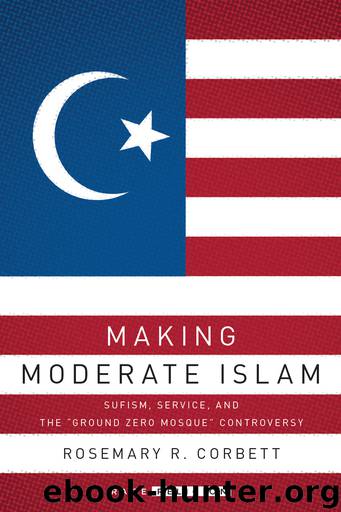

Making Moderate Islam by Corbett Rosemary R

Author:Corbett, Rosemary R. [Corbett, Rosemary R.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2016-04-08T04:00:00+00:00

6

THE PROPHET’S FEMINISM

Women’s Labor and Women’s Leadership

ON A FROZEN FEBRUARY DAY IN 2006, Feisal Abdul Rauf and Daisy Khan worked from the back of a leather-upholstered sedan winding its way across Manhattan to the State Department’s Foreign Press Center on East 52nd Street, where Rauf would film a briefing assuring US diplomats of Islam’s compatibility with American culture, economy, and politics. As the sun began to sink behind Midtown’s office towers, Rauf rested his head against the seat, closed his eyes, and gathered his thoughts. Behind the wheel, Pedram carefully navigated Friday traffic. Meanwhile, Khan read aloud a draft of the press release she would soon disseminate with Lord Carey, the former Archbishop of Canterbury and Rauf’s Council of 100 colleague from the World Economic Forum, in response to the controversy over Danish cartoons that depicted the Prophet Muhammad as a terrorist.1

The conversation in the car turned to the search for someone to speak in Rauf’s place at the mosque during his absences. Dean, a dervish riding along with us, suggested Shaykha Fariha. Rauf hesitated. “We have to be careful,” he said, and informed Dean of the backlash feminist scholar Amina Wadud faced after she led a mixed-gender congregation in prayer in 2005. He also reminded Dean of an incident at Masjid al-Farah in which a knife-wielding man protested both Sufi traditions and that order’s female leadership. Khan stopped typing on her Blackberry to echo Rauf. “It’s true,” she said, giving voice to the hesitations that kept her from supporting Wadud’s activities publically at that time: “people already think we’re too liberal because we’re Sufis.”2

With the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks drawing nearer, American Muslims were increasingly pressed to identify as moderates, particularly on issues of gender, as other Americans (even social conservatives) defined the acceptability of various Islamic traditions by comparing the status of Muslim women to liberal ideals. This was not a new trend in American history.3 While Oprah Winfrey’s unveiling of a burqa-clad woman in Madison Square Garden in 2001 testified to the potency of such images prior to 9/11, justifying foreign wars on the grounds of saving Muslim women was a long-standing colonial tactic.4 Nevertheless, pressure on American Muslims to exemplify moderation by distancing themselves from so-called fundamentalists—not least when it came to issues of women’s roles and rights—increased significantly after the attacks.

Two months after voicing her concerns about ASMA’s image, Khan stood in Union Theological Seminary’s chapel for a “Faith and Feminism” talk—an interreligious program organized by the Sister Fund. Khan was there to inform the attendees about ASMA’s work and to echo Rauf’s message of moderation. On this occasion, promoting women’s religious leadership was central to that message and a crucial way for her to distinguish ASMA from images of Muslims who oppressed women.

Fareena joined Khan at the discussion and also talked about what Sufism meant to her. As she often did when addressing non-Muslims, Fareena spoke of the aesthetic beauty of Islamic art, architecture, and poetry, and of how Sufism made Islam real to her.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15315)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14472)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12359)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12078)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12007)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5757)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5418)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5389)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5290)

Paper Towns by Green John(5168)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4988)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4942)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4482)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4477)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4431)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4380)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4324)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4302)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4179)