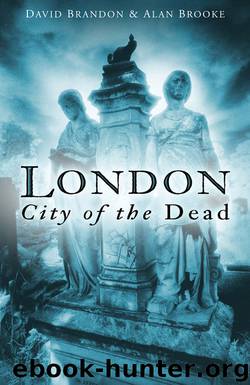

London by David Brandon

Author:David Brandon

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780752496177

Publisher: The History Press

Published: 2013-03-26T04:00:00+00:00

Premature Burial

The dread of being buried alive found expression in literature and burial instructions, such as those left by Lord Chesterfield in a letter to his daughter-in-law on 16 March 1769: ‘All I desire for my own burial is not to be buried alive’. Perhaps the most famous story is that by Edgar Allen Poe (1809–1849), The Premature Burial (1844), in which the sense of absolute terror is vividly portrayed in the book: ‘The unendurable oppression of the lungs – the stifling fumes of the damp earth – the clinging of the death garments … We know nothing so agonising upon earth – we can dream of nothing half so hideous in the realms of the nethermost Hell.’

Poe’s chilling story of premature burial reflected and reinforced a fear that had become pervasive among sections of society during the nineteenth century. Taphephobia – the fear of being buried alive – was mirrored in literature, medical journals, newspapers and in real-life stories. The fears were so real that anti-premature burial campaigns emerged. But what generated these fears? An important factor was the problem of actually defining death. Until at least the seventeenth century when a person died the signs of death were taken to be a cessation of the heartbeat and arterial pulsations. It was common for people not to be examined by a medical practitioner after death. Even in the nineteenth century there were doctors who were incompetent at diagnosing death. The difficulties of diagnosing death provided fuel for well-meaning alarmists who, on the scantiest of evidence, claimed that many people were being buried alive.

Jacques-Bénigne Winslow (1669–1760), the Danish anatomist, argued that the determining signs of death were too uncertain to be relied upon and that the onset of putrefaction was the only reliable indicator that an individual had died. From this conclusion he suggested that people were in imminent danger of being buried alive. He recommended a number of measures to ensure the certainty of death. For example, ‘the individual’s nostrils were to be irritated by introducing sternutaries, errhines, juices of onions, garlic and horseradish.’ He also suggested that gums were to be rubbed with garlic, and the skin be stimulated by the use of ‘whips and nettles,’ limbs could be violently pulled, and the ears shocked ‘by hideous shrieks and excessive noises’; warm urine might also be poured into the mouth. Failing these attempts the corpse might have the soles of the feet cut with razors and then long needles pushed under the toe-nails. Few people aping death would cope with these tests.

There were many cases of people who were believed to be dead but then discovered to be alive, fortunately before they were to be buried. John Stow recorded a case of a man executed for a felony in February 1587. He was taken to the Surgeons Hall near Cripplegate for anatomical dissection and found to be alive, although he only lived for a further three days. Anne Greene was ‘executed’ at Tyburn in 1740 only to recover in the anatomy theatre.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5091)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4791)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4743)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4337)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4189)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4080)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3987)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3965)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3417)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3343)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3320)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3189)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3181)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3140)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3112)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3065)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2913)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2910)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2848)