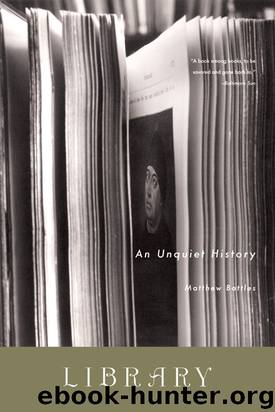

Library by Matthew Battles

Author:Matthew Battles

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2011-03-05T16:00:00+00:00

SWIFT TOO WAS “GIVEN TO PROSE.” In his prescient imagination, however, the figure of the universal library rose prematurely into view; before Swift could satirize it, he had to invent it. The libraries caught up quickly, though. Those tens of thousands of upstart modern troops soon found their places alongside the ancients on the shelves, where they were joined inexorably by an immigrant tide from the ever-busy presses. The wrack and ruin of the library-as-battlefield drowned in the rising tide of the universal library. Swift in his vast humor prefigured the anxiety that Matthew Arnold would express in his 1885 poem “Dover Beach,” in which we are stranded “as on a darkling plain / Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight / Where ignorant armies clash by night.” The bright “Sea of Faith” has finally disappeared from that plain, Arnold writes earlier in the poem, with a “long, melancholy, withdrawing roar.” Parnassus, however, is always reappearing as an island newly reborn, an Avalon or an Atlantis forever discernible in the mists.

Richard Bentley, for his part, continued to run into problems with libraries. Long after the quarrel of the ancients and moderns had fizzled, he installed a young cousin, Thomas Bentley, as keeper of the library of Cambridge’s Trinity College. At Richard’s urging, the young librarian followed the path of a professional, pursuing a doctoral degree and taking long trips to the Continent in search of new books for the library. The college officers, however, did not approve of his activities. The library had been endowed by Sir Edward Stanhope, whose own ideas about librarianship were decidedly more modest than those of the Bentleys. In 1728, a move was made to remove the younger Bentley, on the ground that his long absence, studying and acquiring books in Rome and elsewhere, among other things, disqualified him from the post.

In his characteristically bullish fashion, Richard Bentley rode to his nephew’s defense. In a letter, he admits that “the keeper [has not] observed all the conditions expressed in Sir Edward Stanhope’s will,” which had imposed a strict definition of the role of librarian. Bentley enumerates Sir Edward’s stipulations, thereby illuminating the sorry state of librarianship in the eighteenth century. The librarian is not to teach or hold office in the college; he shall not be absent from his appointed place in the library more than forty days out of the year; he cannot hold a degree above that of master of arts; he is to watch each library reader, and never let one out of his sight (“A slavery,” Bentley writes, “not to be borne by a Master of Arts nowadays”); he is, finally, not permitted a private residence, but must allow a scholar or student to be lodged with him. Bentley concludes by offering, “Your Grace will perceive by these orders, that Sir Edward had in his view a very low notion of His Librarian.”

In encouraging his young cousin to act not as a functionary but as a scholar and a professional, Bentley was once more articulating a library vision strikingly out of step with his time.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32533)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31931)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31923)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31907)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19028)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15912)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14473)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14043)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13840)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13338)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13325)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13224)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9307)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9268)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7485)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7300)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6735)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6606)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6253)