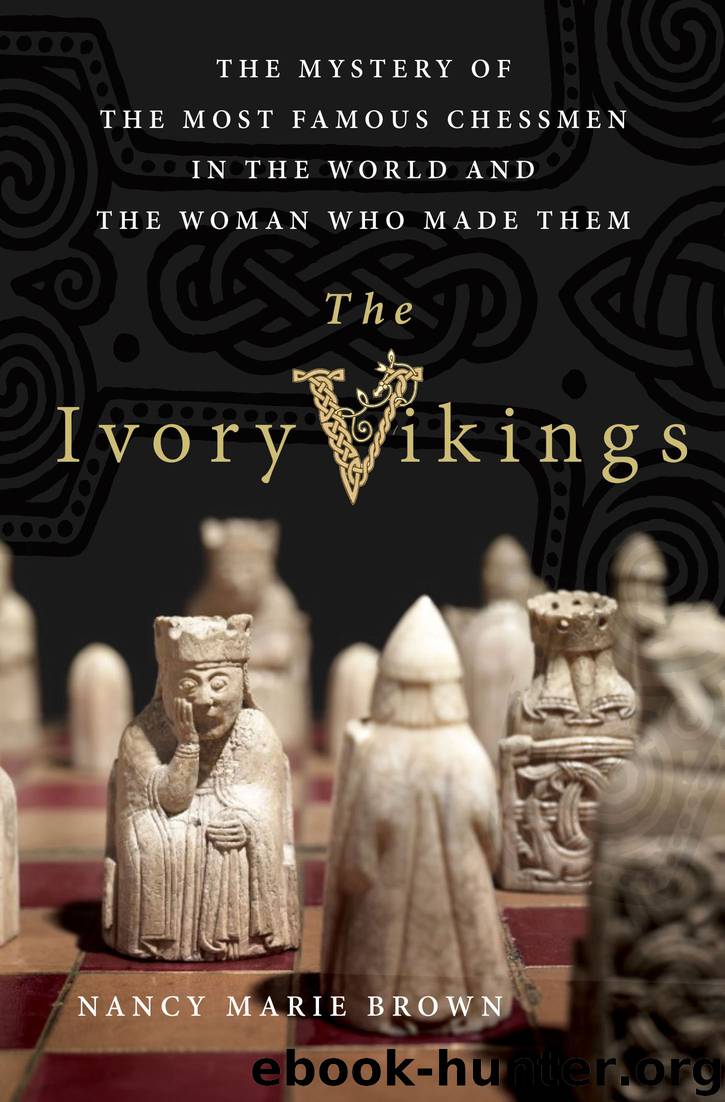

Ivory Vikings by Nancy Marie Brown

Author:Nancy Marie Brown

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: St. Martin's Press

Published: 2015-07-08T16:00:00+00:00

Five

The Knights

The knight is the last piece to place on the chessboard, for knights, as we think of them, in shining armor, were unknown in the North in the twelfth century. All of King Sverrir’s many battles were fought at sea or on foot. Horses, to his warriors, were taxis to the battlefield, not war machines. The warhorse, or destroyer, that could carry a knight wearing sixty pounds of armor, with a lance weighing another forty pounds, the animal itself outfitted in heavy plate, did not yet exist.

In eleventh-century Italy, a Norman knight rode a horse so small his stirrups bumped the ground. French and English horses were no taller, as we can see from the Bayeux Tapestry, sewn about 1075 to celebrate the Norman Conquest. Crusaders’ horses averaged thirteen hands high, or about fifty-two inches at the withers: pony size. In 1200, at the dawn of the Age of Chivalry (named from the French for horse, cheval), the common horse in northern Europe remained “uselessly small.” “Great horses” of sixteen or more hands tall (sixty-four inches at the withers) would not appear until late in the century, after stallions from Central Asia or Spain or North Africa were imported and put to the biggest native mares, and their foals led to graze on watery fens with calcium-rich limestone soil, their diets supplemented further with oats. Until this selective breeding regime took hold, a knight’s mount resembled today’s Icelandic horse, which has remained purebred since the twelfth century. Pony-sized, but strong and agile, Icelandic horses have no difficulty transporting large, heavy men, whose stirruped feet dangle well below the animal’s belly. Even Icelanders acknowledge that it can look ridiculous. A popular cartoon, printed on postcards, shows an Icelandic rider wearing roller skates.

The chessmen’s mounts look “misleadingly” like “stocky, docile ponies,” experts say, and so furnish proof of their carver’s sense of humor. But “stocky” and “docile” are not genetically linked—as anyone knows who’s ridden an Icelandic horse. Plus, the chessmen’s stockiness is functional. A chess knight must be easy to grasp, well weighted and stable, with few protuberances to snap off when the piece is dropped or thrown, or the board overturned in a pique. Artistic license also applies: If the horses’ bodies are disproportionately small compared to their heads, so, too, are the tiny feet of the knights. A chess-piece carver working in walrus ivory, as well, must make a rectangular form (the horse) from an oval-shaped material (the section of tusk) to fit a square space (on the chessboard).

That the size of the horse is not simply a comic touch can be proved, finally, by comparing it to other chivalric images of the time. The knight’s horse on the church door from Valthjofsstad, Iceland, carved in wood with no such restrictions, is significantly more fluid and graceful than the chessmen’s mounts. But it is just as short—as are the horses on an early thirteenth-century enamel from Limoges, France, and a tapestry from Baldishol church in southern Norway.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Channel Islands |

| England | Northern Ireland |

| Scotland | Wales |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(4123)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4122)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3859)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3657)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3532)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3469)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3272)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3078)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(2850)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(2748)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(2741)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(2692)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(2683)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(2655)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2617)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2473)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(2402)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2357)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2286)