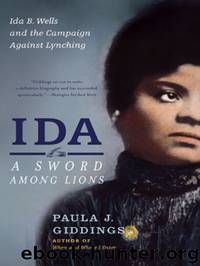

Ida by Paula J. Giddings

Author:Paula J. Giddings

Language: nld

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

IRONICALLY, COMPARED WITH the fireworks at the NACW confab, the actual deliberations of the Afro-American Council meeting, which opened on August 17, were anticlimactic. Although the opening session was so crowded that two women fainted in the eighty-plus-degree weather, the number of voting delegates—fifty, with about half coming from Chicago—was paltry, diminishing the significance of any censure vote. In any case, there was no decisive showdown because Washington, after appearing at the NACW session, did not “darken Bethel’s door,” as one observer put it. His absence was a signal for the McKinley men and the Bookerites to stay away as well.30

Bethel minister Reverdy Ransom was so angered by the turn of events that he offered a bitterly worded resolution, which began by scoffing at Washington for being “comfortably situated in apartments at the Palmer House,” Chicago’s most fashionable hotel, while the Council meetings were debating important issues. “He is a coward and unfriendly to the race,” Ransom insisted. “If Booker T. Washington is the leader of the people why is he not here to lead them?”—a point he would sneer several times before he finished. But Ransom made a strategic mistake when, in his frustration, he also suggested that the absent Margaret Murray Washington be expunged from the roll of delegates. The unchivalrous gesture and Ransom’s tone about both Washingtons rankled the delegates. Du Bois “promptly repudiated Ransom’s unwise attack” and reaffirmed the confidence of the Council in Washington’s “integrity, moral worth, and public service.”31

The scholar’s defense seemed to have calmed the waters, and Ransom later apologized for his remarks. The minister no doubt felt additional pressure to do so from the bishop of his district, Benjamin Arnett, an adviser to McKinley, and who was close to Mark Hanna, the manager of the president’s 1896 campaign and the man responsible for McKinley’s sizable war chest, which had been filled with big-business contributions. Hanna was the point man for Republican patronage and had earlier directed some of the largesse to Ransom when the minister was in Cleveland to help pay off the mortgage of his church. Additionally, the Bethel minister was also preparing to open the Institutional Church in Chicago that would need similar kinds of support. The entire episode was picked up by the Chicago press, which said comparatively little about the Council’s resolutions against racism in the trade unions, imperialist expansion, disenfranchisement, and lynching.32

But the press did pick up the resolution debate about President McKinley and Booker Washington. President Walters, called on to douse another fire, cobbled together some compromise language to save the situation—and, it was speculated, his own presidency. The Council’s resolutions regarding McKinley’s failure to protect black lives and property did contain enough animus for the Cleveland Gazette to observe that they showed “a deep-seated” antipathy toward the administration, which had added insult to injury when McKinley’s vice president, former New York governor Theodore Roosevelt, publicly reversed his earlier laudatory opinion about black soldiers.

At the time of Roosevelt’s recent remarks, blacks, citing their exemplary service in

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32019)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31942)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16029)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14508)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14076)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13370)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13366)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13243)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9344)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9292)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7506)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7314)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6622)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6281)