Gift of the Face by Zamir Shamoon;

Author:Zamir, Shamoon;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2014-03-05T16:00:00+00:00

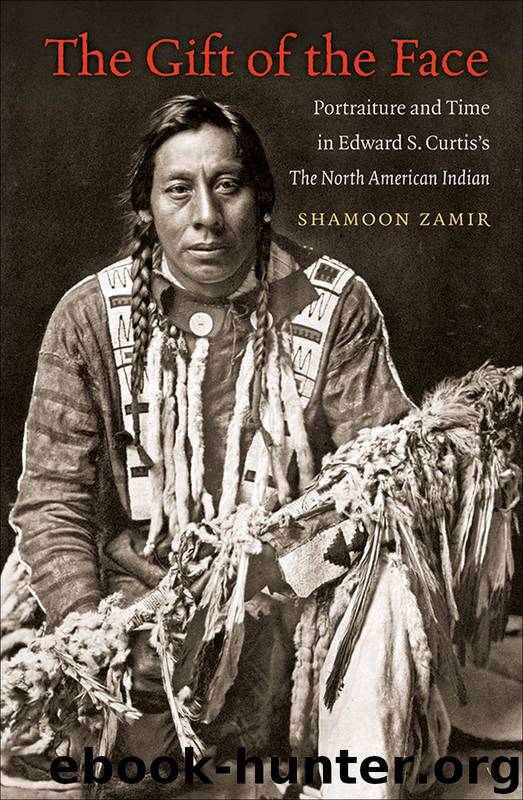

Figure 7.2. Edward S. Curtis, “White Man Runs Him—Apsaroke” (volume 6:portfolio plate 115). Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis’s “The North American Indian,” 2003.

a tangible and still readily available sense of self. Upshaw’s donning of traditional dress lacks such conviction, but this is the truth of his image.

If there is an element of performance in all portraiture, then it is also true that different kinds of performances are involved in the portraits of Upshaw and White Man Runs Him. The image of Curtis’s fieldwork collaborator evinces a degree of ease and familiarity with photographic conventions, and it is this that underwrites the visual effect of a conflicted acculturation. Nothing indicates this better than the contrast between the headdress and necklace worn by Upshaw and the manner in which he leans on his right elbow. Such a pose is a commonplace of Western art (a well-known example being Raphael’s early-sixteenth-century portrait of the courtier Castiglione leaning on a ledge or parapet),37 and it was inherited by the Victorian portrait on both sides of the Atlantic. Individuals lean on chair backs, desks, architectural columns, or any similar object, partly to steady themselves before the slow exposures of the camera and partly to support themselves in composing their faces, while imitating unconvincingly a sense of casual ease. This is exactly the pose Upshaw strikes and it is a pose that never occurs in the other Crow portraits. Yet even as the pose calls to mind Victorian conventions of public and private self-presentation, the large (almost disproportionate) and heavily veined hand in the foreground demurs and ripples the surface of delicacy and decorum; its broad and heavy fingers and its strong knuckles belong with the accomplished celebration of masculinity that characterizes many of the other Crow portraits, while the mottled effects of the out-of-focus outdoor background blend with the delicate feathering of the headdress and actually pull the image away from the vigor of these other images toward an almost incongruous gentility.

Curtis’s image of Upshaw may not represent the normal outward appearance of the man named Upshaw, but its masked quality may represent an aspect of the inner self that is nevertheless true. The very theatricality of the image guarantees its success in simultaneously capturing Upshaw’s ties to and respect for Crow culture while also signaling his distance from it. And Upshaw’s willing participation in the making of the portrait makes plain that he cannot be seen as a manikin posed to display artifacts of ethnographic interest; his performance was the vehicle for a genuine self-expression. Curtis appears to understand something of this sense of self and offers us a subtle visual interpretation of it.

To argue for subtle modulations of meaning in Curtis’s portrait of Upshaw is to suggest that Curtis, as a photographer at least, was sensitive to individual identities and cultural nuances. I want in conclusion to turn for a moment to areas more familiar in Curtis studies, namely, his insensitivity and lack of subtlety when dealing with matters of culture and race.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31333)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21317)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18074)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13109)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12932)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12752)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12451)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11883)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11879)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8350)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7834)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6474)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6406)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5769)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5511)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5037)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4870)