Final Passages by Gregory E. O'Malley

Author:Gregory E. O'Malley

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2014-04-14T16:00:00+00:00

Given the marginality of slavery in New England, one might expect greater reliance on intercolonial deliveries there, but those colonies—especially Rhode Island—stood out from their mid-Atlantic counterparts; several New England merchants plied the transatlantic slave trade in the first half of the eighteenth century, making direct African deliveries to the region feasible. These traders rarely consigned whole shipments from Africa to New England, but they often carried a few people home after selling most enslaved Africans in the plantation colonies. As Rhode Island merchant James Brown instructed his ship captain and brother, Obadiah, in 1717: “If you cannot sell all your slaves [in the West Indies] … bring some of them home; I believe they will sell well.”33 Autobiographer Venture Smith arrived in New England this way; he survived the Middle Passage to Barbados with two hundred fellow captives but was one of just four to remain on board to Rhode Island. Nevertheless, Caribbean transshipments supplemented this African trade to New England throughout the eighteenth century. The account book of ship captain Nathaniel Harris suggests that merchants or slaveholders in the entrepôts sometimes hired captains engaged in intercolonial trade to ship enslaved people to New England for sale. In 1712, “Mr. Nathanael Humphry of Antigua” paid Harris to deliver two captives from that island to Boston and to sell them on his behalf. Harris earned four pounds sterling for the “freight of 2 Negro’s” from Antigua to Boston, reimbursement for the import duty on them, and a “Commission for Selling the Negro Man” of just less than two pounds. The other enslaved person apparently remained in Harris’s possession at the time the account was recorded.34

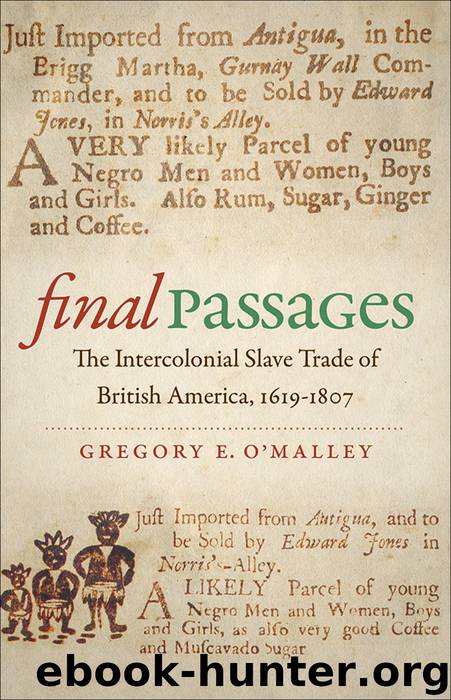

Northern colonies resembled North Carolina and Georgia in their reliance on intercolonial deliveries of Africans, but the northern colonies did not lack the capital to attract merchants. Instead, transatlantic slavers ignored them because they lacked a major reliance on slavery. This fundamental difference gave their branch of the intercolonial trade a different character. Most notably, merchants proved willing to speculate on small slaving ventures from the Caribbean to the North, and because demand was not pent up, they had to be aggressive in marketing. This offshoot of the intercolonial slave trade was especially appealing to merchants because the northern colonies’ export of provisions to the Caribbean made a return trip with African people a viable corollary. As exports of flour, salted fish, and timber to the Caribbean grew increasingly important, return shipments brought rum, sugar, and tropical fruits. Especially at times when abundance limited the prices for such Caribbean commodities, transshipments of enslaved Africans offered a compelling alternative. Hence, advertisements for enslaved Africans in the North generally offered the people in small groups alongside Caribbean produce, at the home or store of a New England merchant or, less frequently, aboard the ship that carried them. In 1739, Philadelphia’s American Weekly Mercury printed Captain Benjamin Christian’s advertisement of “two verly [sic] likely Negroe Boys … [and] Also a Quantity of very good Lime-juice.” Willing, Morris, and Company

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15365)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14522)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12403)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12101)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12035)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5795)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5454)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5410)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5312)

Paper Towns by Green John(5195)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5013)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4966)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4508)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4493)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4451)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4398)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4353)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4330)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4207)