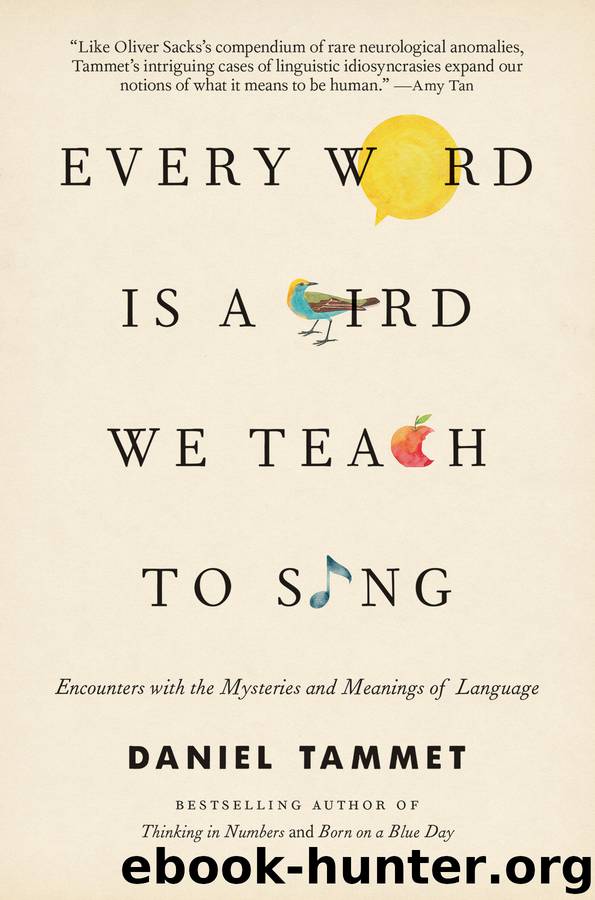

Every Word Is a Bird We Teach to Sing by Daniel Tammet

Author:Daniel Tammet

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Language Arts & Disciplines / Linguistics / General, Philosophy / Language, Social Science / Essays

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Published: 2017-09-11T16:00:00+00:00

Hví svo þrúðgu þú

þokuhlassi,

súlda norn!

um sveitir ekur?

Þjér mun eg offra,

til árbóta

kú og konu

og kristindómi.

[Goddess of drizzle,

driving your big

cartloads of mist

across my fields!

Send me some sun

and I’ll sacrifice

my cow—my wife—

my Christianity!]

Moreover, the naturalist showed a remarkable aptitude for inventing new words, words made out of existing words, without having to borrow sounds or notions from the obliging French, Greeks, or Danes. Aðdráttarafl (“magnetic force,” literally “attraction power”), fjaðurmagnaður (“supple,” literally “stretch-mighty”), hitabelti (“the Tropics,” literally “heat-belt”), and sjónarhorn (“perspective,” literally “sight corner”) are only a few of the hundreds with which he endowed the language. Then, in 1845, he died at the age of thirty-eight, and his naively bucolic vision of his countrymen as wise farmer-citizens became forever fixed.

Icelandic is self-sufficient: this became the cry of the nationalists seeking independence from Denmark. Poetry reduced to politics. In 1918, independence came. But the aftereffects of Hallgrímsson’s naive vision persisted. The national obsession with rooting out every trace of foreign influence in the language grew fierce. So fierce that from time to time government campaigns would lecture citizens on how to tell Icelandic, Danish, and other foreign words apart. Listen to tónlist (literally “tone-art”), newspaper readers were crisply informed, not músík. Take your shower in a steypibað (literally “pour-bath”), not in a sturta. Smart, the Danish way of describing someone or something as “tasteful,” was repudiated in favor of smekklegt. And as technology expanded and the world shrank, the purists’ efforts only intensified. The minting of brand-new words became a full-time occupation. Since the 1960s, the country’s universities regularly put their eggheads together to rationalize the work. (The minutes of their meetings, like those of the Persons’ Names Committee, are currently written by Jóhannes.) The work also includes keeping tabs on the media, lest a foreign word—these days, usually English—supersede any Icelandic coinages. Upbraiding fingers will be wagged at the television or radio presenter who forgets to say jafningjaþrýstingur instead of the current peer-pressure.

It is the paradox of the Romanticists’ struggle that, though it was supposed to free the Icelander of all anxiety to perform, as well as erase any standards of speech beyond those words and sounds that come naturally to mind and tongue, the result has been quite the opposite. The poet and his pastoral vision, creating the ideal speaker, also created a new linguistic standard and divided the nation’s consciousness. When those who live far from the countryside in the capital, as two-thirds now do, catch themselves saying something from an American film, or a British pop song, they cringe. Some undergo a linguistic crisis and yearn for the best, the purest Icelandic, that Icelandic of Icelandics still spoken out in the sticks, to communicate authentically. It is of this yearning, the narrator’s, that the popular, prizewinning novel Góðir Íslendingar (Fellow Countrymen), published in 1998, speaks: a forlorn young Reykjavík-dweller discovers a certain dignity—of speech, and thus of character—only among the isolated country folk (the translation is mine):

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32540)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31936)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31927)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31914)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15931)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14479)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13881)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13342)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13339)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13229)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9313)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9272)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7487)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7305)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6744)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6610)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6261)