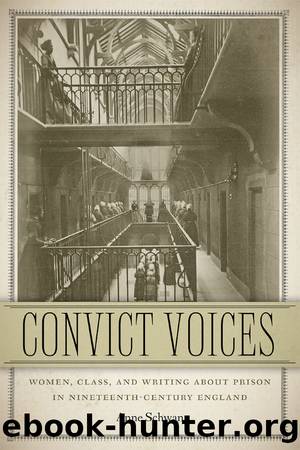

Convict Voices by Schwan Anne;

Author:Schwan, Anne;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of New Hampshire Press

FIGURE 5.1 Florence Maybrickâs âCriminal Court Procedure in England and Americaâ in the New-York Tribune Sunday Magazine, 22 Jan. 1905

Echoing Gail Hamiltonâs furious attack on old-world barbarism, Maybrick similarly constructs America as a progressive, enlightened nation where the âunfortunateâ are treated in an âaltogether humane wayâ (âCriminal Court Procedureâ). This journalistic critique of the English criminal justice system complements Maybrickâs complaints in her autobiography, in which, despite her admiration for her defense counsel, Lord Russell, she speaks in no uncertain terms of her dissatisfaction with her adopted countryâs legal system, concluding, âIt looks as if justice in England were growing of late more than ordinarily blindâ (Own Story 154). Contrasting the English government with the English people, the American writes, âThe supineness of Parliament in not establishing a court of criminal appeal fastens a dark blot upon the judicature of England, and is inconsistent with the innate love of justice and fair play of its peopleâ (89). Through her lengthy discussion of the case of the Norwegian Adolf Beck, in the words of one commentator âan innocent and inoffensive foreignerâ who was convicted twice for crimes committed by somebody else, she further emphasizes nationality as a contributing factor and lends credence to her own account of American innocence unjustly condemned (159).32

In the âCriminal Court Procedureâ article, Maybrick, by declaring âpride in [her] countrymen,â arguably mobilizes a nationalist rhetoric to firmly reposition herself from former pariah to patriotic citizen who deserves her hard-won place in the bosom of her nation. Through an analysis of English court architecture and protocol, which she reads as a reflection of social hierarchies, she affirms the democratic values promoted in the US Constitution as opposed to the autocratic power enjoyed by the English judge, who represents âthe personified majesty of the law.â Ironically, the accompanying illustration of âMrs. Maybrick on Trial,â reprinted from the London Graphic, undercuts this argument by emphasizing the female defendantâs imperious presence in the center foreground, while the judge appears diminutive in the background (see figure 5.2). Maybrickâs celebration of Americaâs supposed egalitarianism is further undermined by her dismissive comments about the constitution of her ââcommonâ juryâ elsewhere, comments which betray her classist attitudes.

Throughout the article, similar to the autobiography, Maybrick walks a fine line between asserting female independenceânot least by speaking out in publicâand promoting the necessity for paternalistic support for falsely accused women, for example, by highlighting the role of Pattersonâs âaged fatherâ during the trial: âher white-haired, natural protector was ever by her side to cheer and support her.â Reflecting on the selection of the jury, she concedes that not all women may be able to choose âin their own interestâ but also insists that womenâs âintuitionsâ can and should be brought to bear. Close in tone to the spiritualist Fletcherâs call for a female defendantâs right of active involvement, Maybrick concludes that regardless of womenâs qualifications for making informed legal choices, a sense of ownership in the process is key: âthere surely is something satisfying in the mere thought that you have not been dragged to your doom.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32562)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32022)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31959)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31945)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19052)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16047)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14520)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14161)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14081)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13376)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13375)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13247)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9347)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9297)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7508)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7316)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6769)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6626)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6284)