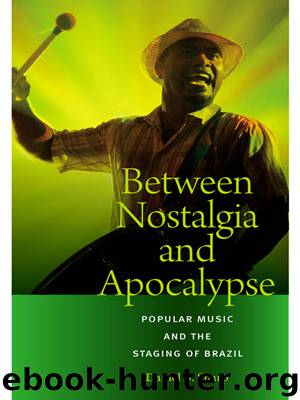

Between Nostalgia and Apocalypse by Sharp Daniel B.;

Author:Sharp, Daniel B.;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Wesleyan University Press

Published: 2014-04-11T04:00:00+00:00

A Favela Light in the Sertão Light: Afro-Pernambucan Tourism and the Cosmetics of Hunger

Middle- and upper-class Brazilians going up a hill to visit a favela to “drink from the source” is a practice embedded in the lore of Brazilian popular music at least since Noel Rosa’s success helped nationalize and popularize the practice in the 1920s and 1930s (Vianna and Chasteen 1999, 87). A scene in the film Rio Zona Norte (1957) dramatizes the practice of slumming in the hilltop shantytowns of Rio de Janeiro. Arcoverde’s recent cultural tourism boom combines a rural sojourn associated with the saint’s days in June with an urban trek up the hill to dance in a poorer neighborhood.

Several factors converged in the late 1990s, above and beyond the distinctive and powerful voices of Coco Raízes and Cordel, to create a shift in the town’s visibility. One broad national trend regarding race and national identity in the postdictatorship 1990s was the persistent questioning of the consensus that social celebrations such as samba musically reproduce and represent the harmonious integration of races and social classes in Brazil. Assertions of black cultural difference stemmed from the black movement’s questioning of the rhetoric of racial democracy and celebration of racial and cultural mixture. The popularity of hip-hop and funk among favela youths is seen by Yúdice as one such indicator of this “disarticulation of national identity” (2003, 114).

In addition, since the 1980s in the northeastern city of Salvador, Bahia, musical expressions of Afro-Brazilian identity have quickly proved highly lucrative for cultural tourism by both domestic and foreign visitors. Coco Raízes’s alliances with coastal coco and afoxé groups and the participation of Damião Calixto and some of his immediate family in a local umbanda terreiro point to the group’s links with the Afro-Brazilian religious and activist communities. In this neoliberal multiculturalist context, Arcoverde’s municipal government had different reasons to emphasize Afro-Brazilian cultural manifestations in the interior sertão. For the tourism bureau, placing samba de coco on the town’s campaigns of self-promotion was a way to differentiate their São João celebration from those of larger nearby cities such as Caruaru and Campina Grande, who market the event with the rural kitsch of white and mestiço hick clowns dancing to forró and quadrilha. Arcoverde attracted a younger, more fashionable musical visitor from Recife who enjoyed the Afro-Pernambucan elements in Recife’s Carnaval and the rooted cosmopolitanism of the state capital’s post–mangue beat new music scene. Arcoverde has been called sertão light, because of its relatively amenable climate, nestled in a small valley on the edge of the desert. A journey away from the urban tension of Recife to the Alto do Cruzeiro can be seen as a visit to favela light5 in the sertão light, where one can “drink from the source” safely and comfortably, enjoying warm, small-town hospitality and spontaneous musical performances. If times have changed, and the semblance of harmony between races and classes is increasingly difficult to sustain in the urban space, this movement to the hinterlands can be

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15365)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14522)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12403)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12101)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12035)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5795)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5454)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5411)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5312)

Paper Towns by Green John(5195)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5013)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4966)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4508)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4493)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4451)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4398)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4353)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4330)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4207)